Nearly 35 years have passed since John Evers Robinson was found dead in his New Haven, Connecticut music studio. The original investigation generated several leads and theories of the killing, but the case remains unsolved. Now, John’s sister is doing everything she can to get her brother’s story out there. Someone knows something. It’s time to speak up.

If you have information regarding the 1990 murder of John Evers Robinson in New Haven, Connecticut, please contact the Connecticut Cold Case Unit at 1 (866) 623-8058 or the New Haven Police Department at 1 (866) 888-8477.

The Discovery

It was just before 8:30 in the morning on Wednesday, March 14, 1990 when firefighters responded to 178 Temple Street in New Haven, Connecticut. Visitors and tenants in the building had noticed a strong foul odor emanating from the direction of room number 208. When they peered through the mail slot on the door, they could make out the shape of a person laying on the floor and they swiftly called 9-1-1.

First responders arriving at room 208 found one of the door’s two deadbolt locks engaged and so they gained entry by removing the door from its hinges. A paramedic then crossed the dark room to hoist open a window, allowing fresh air and light to flood the small space and revealing the full scope of the devastating scene.

The body of a man was lying face down on the floor, the victim of apparent severe head trauma. Whatever happened here was brutal and violent. Seeing the condition of the person, the paramedics and other first responders vacated the room and waited for police to arrive.

A detective spoke with the property manager of the building to figure out who the victim might be. The property manager explained that the space was known to be used as a music studio and a check of lease documents showed that the deceased was likely the tenant, a local musician. Receipts found in the pocket of a coat at the scene were more confirmation: This was 24-year old John Evers Robinson.

About John Robinson

John’s sister, Jocelyn Jackson, has become the voice of his story. She was just 15-years old when he was killed, but she remembers him through a vibrant patchwork of firsthand experiences with her caring, silly older brother stitched together with the stories she’s heard from other family members and John’s friends.

“Those memories are almost always, there’s laughter in them,” Jocelyn began. “Because, you know, the hijinks of an older brother is just what it is. It’s the tickle fights in the family room. It’s the playing with the dog in the front yard. It’s helping my mom run for a board of education and like painting signs together.”

Jocelyn remembers her brother as a caretaker; a protector. He looked out for her and those he cared about. He was also someone who got an idea and went for it, full steam ahead by any means necessary. Whether it was learning how to make a souffle – eggs upon eggs sacrificed in the process – or as a teenager, leaving the life he knew in Kansas with his mother and Jocelyn to move in with his father in Connecticut.

John moved into Yale University housing with his father, where he was in a graduate program at the time. John himself was accepted to a private high school. He explored science and art and sports but the passion that really took hold and continued well past high school was music.

John played bass and his genre of choice was punk, though Phil Gallo described John’s music in the New Haven Register as more hardcore.(8) He and a rotating line up of musicians formed a band in 1986 most commonly known as Sold on Murder, or just SOM. John’s nickname on the scene was “Rokked”.

Jocelyn remembers listening to her brother’s music on cassette tape as a kid.

“Having that cassette tape was sort of a really sweet way to be a part of John’s life. I admit that the punk is hard,” Jocelyn laughed, “It took more of my adult years to go into a place of appreciation for the musicality.”

You can hear John’s music for yourself. A posthumous album released by his friends and family is available to stream for free.

Jocelyn shared, “Through his music, you’ve found his stories and experience of politics and of social justice and of the messages in music often tell so much about someone’s life and their commitments. And so I think that was the other way that he was able to share his vision for the world for his own place in it is that he wanted to have a liberatory sort of approach to the world.”

The punk scene in New Haven, Connecticut in the 1980s was a vibrant, gritty subculture shaped by the era’s anti-establishment sentiment and a rebellious spirit that mirrored the broader punk movements across the United States.

As Jocelyn said, “It was powerful to see how my brother lifted himself up in an environment that often was not populated by Black folks.”

“It’s so profoundly clear that he had an unassailable commitment to music and to being a musician and that playing out gig work, finding the way to bring the songs that he wrote into the world was such a clear focus for him,” she explained.

Nearly all of John’s energy and resources were poured into his band and their efforts to record and release an album. John rented room number 208 at 178 Temple Street in downtown New Haven, which he commonly referred to as “the loft”, for a recording and practice space for the band. He also sublet the studio by the hour, collecting a small fee from other musicians.

Though it was not intended for residential use, John may have been staying at the loft on and off, too. He had fallen behind on rent at the apartment he shared with a few roommates and had been asked to move out.

“He was often houseless,” Jocelyn said. “He was finding a way to make money, live his life, and also make music. And sometimes that was staying on people’s couches. Sometimes he had his own apartment. And he was always just trying to figure out, how they say, make ends meet in order to keep making music.”

For work outside of playing shows with his band, John was a manager at Ashley’s Ice Cream in New Haven. The job came with a paycheck and access to the ice cream delivery truck for lugging the band’s gear around to venues for gigs. It was just another way John used what he had to support his dreams. But as Jocelyn has learned, her brother also took some risks.

“As I’ve heard from friends, one of the ways he entered into drug culture was trying to find money through that as a way to fund his music. That’s heartbreaking to me that that was his choice. And I know the realities of the eighties as well. And I know that that time was sort of rampant with drug culture.”

Sources indicate that John was known to buy and sell small quantities of pot to friends and Yale students. However, as the early investigation would reveal, John was making plans for a bigger buy and other individuals had put money on the line with him, too. The details of this deal, and other potentially volatile situations John was involved in, came to light as police began to interview John’s friends and acquaintances.

John Evers Robinson’s story continues on Dark Downeast. Press play to hear the full episode wherever you get your podcasts.

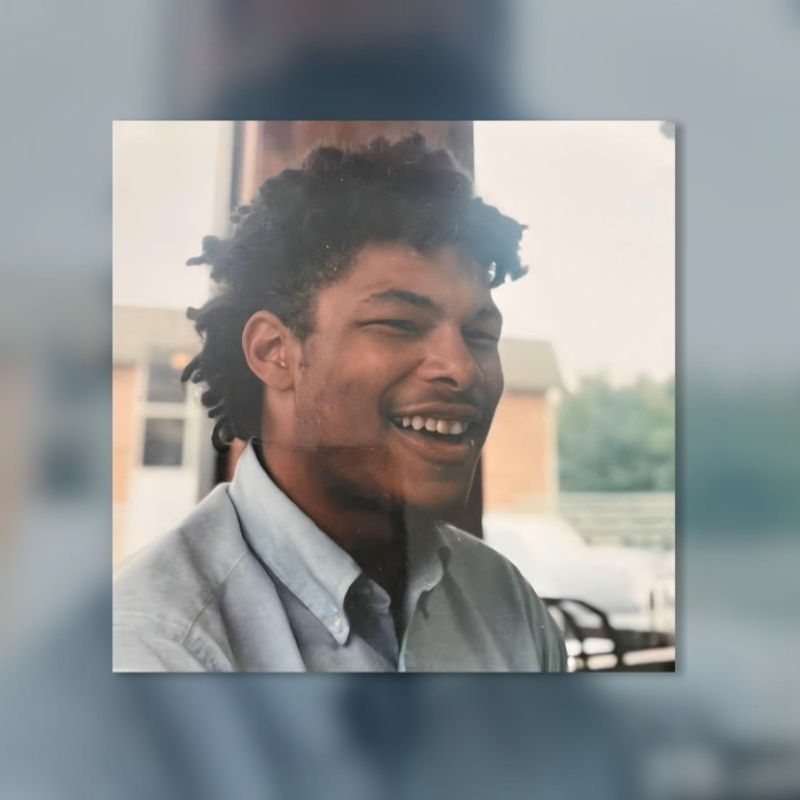

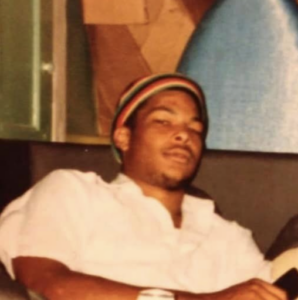

John Evers Robinson, All photos courtesy of Jocelyn Jackson. See more at soldonmurder.com.

John Evers Robinson, All photos courtesy of Jocelyn Jackson. See more at soldonmurder.com.

John Evers Robinson, All photos courtesy of Jocelyn Jackson. See more at soldonmurder.com.

John Evers Robinson, All photos courtesy of Jocelyn Jackson. See more at soldonmurder.com.

Episode Source Material

- New Haven Police Department 1990 Case File Documents for John Robinson’s Case

- Sold On Murder, Podcast by Jocelyn Jackson

- Cultivating the cults by Phil Gallo, New Haven Register, 05 Feb 1988

- Bludgeoned man expected death by Michael Foley, New Haven Register, 16 Mar 1990

- John E. Robinson, found dead in office, New Haven Register, 17 Mar 1990

- Friends bid goodbye to beloved ‘Rokked’ by Paula Brackenbury, New Haven Register, 18 Mar 1990

- Stumped cops ask public to help solve murder by Michael Foley, New Haven Register, 22 Mar 1990

- Sold on Murder: The life and death of a rebel without a cause by Howard Altman, New Haven Advocate, 02 Apr 1990

- Spotlight: Musician’s slaying sparks reward offer, New Haven Register, 03 May 1990

- City slayings claimed these 31 victims in ‘90 by Michael Foley, New Haven Register, 06 Jan 1991

- 32 years later, a murder resonates anew by Laura Glesby, New Haven Independent, 10 Mar 2022