In a one month span during the winter of 1969, the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts was set on edge after two violent attacks on women while they slept in their beds challenged the very sense of safety residents thought they had in their own homes.

Nearly 50 years later, one of those cases was finally solved, but the second, very similar homicide is still waiting for answers. The case file for the homicide of Ada Bean shows that the investigation uncovered numerous leads and tons of evidence at the time, but none of it led to an arrest. After more than five decades, this story is long overdue for an ending.

The Discovery

It was Thursday morning, February 6, 1969 and Robert Druckman had his eyes trained on the door waiting for his co-worker 50-year old Ada Bean to arrive. The last time anyone in the office saw her was when she left work at 5 p.m. on Tuesday that week. Each minute that ticked by only raised his concern further, and Ada’s boss began to take notice, too. Ada was a reliable employee, and it didn’t make sense that she would no-show two days in a row. Finally, the boss asked Robert to stop by Ada’s apartment to make sure everything was alright.

Ada’s apartment building at 41 Linnaean Street in Cambridge was a stately brick building with 32-apartments and an on-site superintendent to tend to the needs of tenants and coordinate the upkeep both inside and out. When Robert arrived, he tracked down the super, James Edwards, and explained that he was worried about Ada. Together, they walked up to the third floor to apartment 38.

They knocked several times, calling out Ada’s name, but no one answered. So, James used his master key to let Robert into Ada’s apartment. The bedroom, which was more of an alcove mostly open to the rest of the apartment, was visible from the front door so he only needed to take one step inside to see Ada lying motionless on the bed and blood all over her room.

Robert immediately stepped back into the hallway and closed the door behind him. He told the superintendent that they needed to call the police, right away.

About Ada Bean

Ada Caroline Bean, born Ada Bradbury on February 17, 1918, grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts where her father Harold M. Bradbury was a local politician. He’d served two terms in the Massachusetts Legislature and was a member of the Cambridge Common and City Councils. Her uncle was also the mayor for a time, so the Ada’s family was pretty well-known in town.

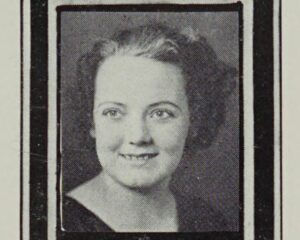

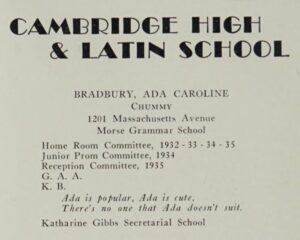

Ada attended Morse Grammar School and then graduated from Cambridge High and Latin School in 1935. Her senior yearbook shares the many committees and clubs Ada was part of, including Junior Prom Committee and the Senior Reception Committee. Next to the photos of each graduating senior, there’s a short rhyme which seems like it was written by someone on the yearbook staff. For Ada, the poem goes, “Ada is popular, Ada is cute, there’s no one that Ada doesn’t suit.” Her future plans are listed as Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School.

The Gibbs School was an academy that only admitted women and provided training in typing, spelling, grammar and social etiquette. Though it feels outdated now, a paper by the Cambridge University Press explains that these secretarial schools were a rare avenue for women in the early decades of the 1900s to build a career and establish independence during a time when that wasn’t necessarily the norm.

So, after completing her secretarial studies, Ada got her first job in June of 1936 at a property management company in Harvard Square. She helped with the bookkeeping and rental of apartments all over Cambridge for four years until she met the man who would become her husband, Frank Bean. They were married in October of 1940. Their son Frank Jr. was born in December of 1945.

Sadly, Frank Sr. passed away just three months later in March of 1946. Ada was suddenly a 28-year old widow and single mother to an infant. Within a few months, she returned to the workforce for the first time since she was married.

Two versions of Ada’s self prepared resume are contained in the Cambridge Police Department file for case number 69-877. It’s nothing like the one-pagers you might be used to seeing today. This multipage document she typed up is like a chronology of her adult life. Ada’s first job after Frank Sr. passed away was serving as a secretary to the counselor of veterans at Harvard University. In the two years she worked there, Ada writes that she became a walking encyclopedia of government rules and regulations.

Each position thereafter held more responsibility and earnings than the last. She worked in several other offices of Harvard University as well as a national company that had her traveling out of state to oversee projects and conventions. It’s obvious that her work ethic and skills were valued everywhere she decided to take them, but her biggest focus of all always came back to her son.

In one section of her resume, Ada mentions how certain choices she made in her career were so she could spend more time with Frank Jr. and better support her family as a single parent. When her son was around 9-years old, Ada decided to rent out four rooms in her house to graduate students studying at Harvard. The extra rental income allowed her to drop down to part-time work. She writes, quote, “I worked only mornings and was able to be at home afternoons to direct my son’s activities. This I enjoyed…” End quote.

But by 1969, with her son all grown up, married, and with a child of his own, Ada returned to full-time work. She was a secretary for Associated Business Machines on Belmont Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. That’s where she should’ve been on February 6, if not for the terrible tragedy discovered by a fellow employee that same morning.

Early Investigation

Cambridge Police arrived at 41 Linnaean Street around 9:45 a.m. and were greeted by Ada’s co-worker Robert and the building superintendent James Edwards. James lead officers up the stairs to apartment #38 and pointed straight ahead to the bedroom. James stayed behind in the hall as the officers crossed the threshold and proceeded into the small room. To the right, they saw Ada’s lifeless body lying on her twin size bed. She was nude from the waist down with blankets, sheets, and clothing piled up and pulled over her torso and face.

According to a handwritten report in the case file, one officer used his pen to lift the blankets covering Ada’s face. Beneath them, he saw she’d been violently beaten. Her face and head were covered with blood and it had saturated the sheet and pillow underneath. Glancing around the room, the officers noticed the walls and floor were splattered with blood and a pool of it had collected on the floor beneath the bed.

The officer lowered the blankets back down and stepped into the hallway in search of a phone. Using a handkerchief to ensure his prints didn’t inadvertently end up at the scene and protect any others already there, he picked up the receiver and dialed headquarters to notify his Lieutenant what they’d found. Lt. Delaney of Cambridge PD requested a canine officer respond to the scene, as well as evidence technicians and fingerprint experts, a photographer, and the medical examiner.

As they waited for the other units to arrive, the two officers surveyed the rest of the scene. Two wide open crank-out windows took up most of the wall on the far end of the bedroom opposite the door and the drapes flanking either side of the windowbank were blowing in the wind.

A dresser on the left side of the bedroom was topped with a lamp and hairbrush and hand mirror, a few photos of children, and some cosmetics. Near the foot of the bed was a wooden stool with a tipped over wind-up alarm clock, still ticking, a pack of Kool cigarettes, matches, and an ashtray with one cigarette butt about three-quarters in length with no ash. In the living room, a pile of clothes was sitting neatly folded on a chair. Nothing seemed to be disturbed in any way and there didn’t appear to be any signs of a struggle. Police surmised that Ada had been attacked in her sleep.

The two officers checked the other doors in the apartment and found a second entrance door off the kitchen was closed but not latched or locked and they didn’t have to turn the handle to open it. It looked as if it had been previously tampered with or forced open. One of the officers followed the staircase off the kitchen door down to the basement of the building and cleared the area, not finding any sign of an intruder hiding out down there. However, he did find that an exterior door off the basement was also unsecured – either it didn’t have a lock or the lock was broken.

Soon, 41 Linnaean street was swarming with investigators. Montgomery Talbot, the assistant chemist for the Massachusetts Chemical Laboratory, surveyed Ada’s apartment and noted the bloodstains on the ceiling and all four walls of the bedroom. He also performed a benzidine test on several surfaces, which detects the presence of blood, and found trace blood on the bowl of the bathroom sink. Fingerprint technicians worked at the scene simultaneously, dusting surfaces and objects for latent prints.

Other investigators collected several items from around the apartment, including one cigar butt and that cigarette butt, a white shirt, a tweed sport coat, and the wooden handle of a hammer. Later, police also delivered to the lab for testing a wooden handled screwdriver and a brass striker plate from the door jamb off Ada’s kitchen.

Meanwhile, patrolman Edward MacAskill and his search dog, Champ, had arrived at the scene. Champ sniffed around Ada’s bedroom and then seemed to pick up a trail, turning around and tracing it to the kitchen and then out the front door of the apartment. Once in the hallway, the dog made a left turn and sniffed all the way to the far end before doubling back and sniffing down to the other end of the hall. Officer MacAskill reset the dog a second time, but Champ followed the same path again.

Officer MacAskill brought Champ back into Ada’s bedroom and directed him to specifically identify a scent trail starting from the bed and sheets. This time, Champ tracked the scent into the kitchen and then through the secondary exit down the back staircase and into the basement. The dog paused for a moment and then seemed to pick up the scent again, sniffing his way over to the basement exterior door leading onto Avon Hill Street. The dog continued outside and onto the sidewalk and then stopped.

When Officer MacAskill brought Champ back upstairs for another attempt with a scent from a different part of the bed, the dog again followed the trail through the kitchen and down the back staircase but turned around and instead of following it out the exterior door, he climbed a different staircase, stopping at a door that led into the third floor hallway. The officer then tried to see if Champ could pick up a trail from the sidewalk, but the dog didn’t respond. Later that morning, a second search dog also tracked a scent from Ada’s bedroom and down the back staircase to the basement and then up another stairwell to the third floor.

Based on the trail indicated by both of the tracking dogs, and the fact that the rear door to Ada’s apartment in the kitchen appeared to be tampered with, investigators hypothesized that whoever killed Ada likely got into the building through the unsecured exterior door in the basement and then forced their way in through the kitchen entrance, undetected.

Police were having a hard time tracking Ada’s movements after she left work on Tuesday, February 4th. According to reporting in the Boston Herald, Ada’s niece told police she spoke to her aunt on the phone around 8:30 p.m. that night and that was the last time anyone heard from her. Based on the time of that call and Ada’s absence from work on Wednesday the 5th, investigators believed she was killed either late Tuesday night or early Wednesday morning, more than a day before she was finally found on Thursday.

Medical examiner David Dow and forensic pathologist Dr. George Katsas performed Ada’s autopsy, and that range for the time of death more or less fit their findings. The examination also revealed that Ada sustained extensive lacerations of her forehead and scalp with partial avulsion of her scalp. She had a fractured skull so severe that portions of her brain were exposed by the injuries. Dr. Dow ruled that Ada’s death was the result of multiple comminuted fractures of the skull with laceration of the brain. He believed the weapon was a blunt instrument, and her manner of death was undoubtedly a homicide. In the source material I have, there’s no mention of any findings of sexual assault.

Ada’s clothes were collected and sent to the lab for testing along with all of the other evidence recovered from the scene as investigators began their interviews with neighbors, friends, family members, and other potential witnesses.

Call to Action

Anyone with information relating to the unsolved homicide of Ada Bean can contact the Massachusetts State Police detective assigned to the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office Cold Case Unit at (781) 897-6600.

I also invite you to contact the District Attorney’s Office and ask about the status of Ada Bean’s case. Copy and paste the message below into the contact form here.

District Attorney Marian Ryan,

I am writing to request an update on the investigation into the 1969 homicide of Ada Bean in Cambridge. Specifically, I’d like to ask about any ongoing or forthcoming DNA testing, Y-STR analysis, or genetic genealogy efforts concerning evidence recovered at the scene and other recent investigative efforts. Your prompt attention to this matter is greatly appreciated, and I eagerly anticipate your response. Thank you.

Mentioned in this Episode

Ada Bean. Source: Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, 1935

Ada Bean (Bradbury) senior yearbook photo. Source: Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, 1935

Ada Bean (Bradbury) senior yearbook profile. Source: Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, 1935

Ada Bean pictured with the Klawhowjaha Bjustoff Club. Source: Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, 1935

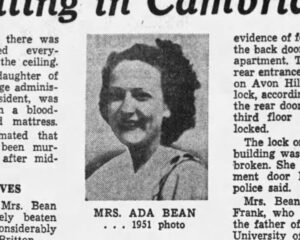

Ada Bean as of 1951. Source: The Boston Globe

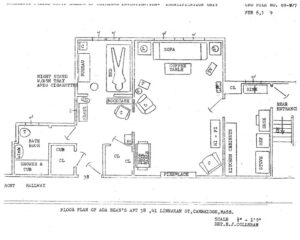

Sketch of the crime scene in Ada Bean’s apartment. Source: Cambridge Police Department/Middlesex District Attorney’s Office

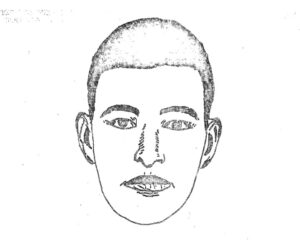

Composite sketch of man seen in the hallway of 41 Linnaean Street on the night of Ada Bean’s murder. Source: Cambridge Police Department/Middlesex District Attorney’s Office

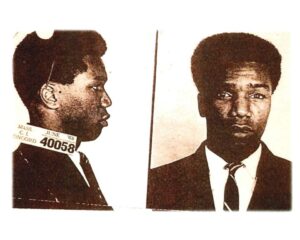

Booking photo of Michael Sumpter, suspect in Jane Britton’s murder. Source: Middlesex District Attorney’s Office

Episode Source Material

- Cambridge Police Department File No.69-877, Ada Bean, February 6, 1969

- Cambridge woman murdered, AP via The Lowell Sun, 06 Feb 1969

- New bludgeon death in hub apartment, AP via Fitchburg Sentinel, 06 Feb 1969

- Widow 2nd Cambridge victim of bludgeoning in month by Jeremiah V. Murphy, Boston Globe, 07 Feb 1969

- Police hunt murder tool, Boston Globe, 07 Feb 1969

- 2 murders in Cambridge seen similar by William McCaffrey and W. J. McCarthy, Boston Herald, 07 Feb 1969

- Cambridge widow vitim: New bludgeon murder, Boston Record American, 07 Feb 1969

- Widow bludgeoned to death, AP via The Recorder, 07 Feb 1969

- Peeping Tom sought in Cambridge, AP via Greenfield Recorder Gazette, 08 Feb 1969

- Cambridge murder suspect is sketched, Boston Herald, 08 Feb 1969

- Cambridge man sought in window’s murder by Ed Corsetti and Bull Duncliffe, Boston Record American 08 Feb 1969

- Police in Cambridge query neighbors of Slain woman, UPI via Holyoke Daily Transcript, 08 Feb 1969

- Ada C. Bean Obituary, The Boston Globe, 08 February 1969

- Search Begun For Suspect in Cambridge, Associated Press via The Berkshire Eagle, 08 February 1969

- Police quote “I think it still is a little too soon to say” re: suspect

- Cambridge Slay Suspect’s Picture Drawn, The Boston Globe, 09 February 1969

- Cambridge police hunt slay suspect, Boston Herald, 09 Feb 1969

- Widow slay suspect’s photo circulated by Ed Corsetti and Joe Giulitotti, Boston Record American, 09 Feb 1969

- Council offers reward in slaying of woman, Boston Record American, 12 Feb 1969

- Good Leads In Bean Murder, Associated Press via The Recorder, 13 February 1969

- 2 fires found where woman slain earlier, Boston Globe, 13 Feb 1969

- 6 Fires Hit Site Where Widow Slain by The Boston Globe, 14 February 1969

- 6 fires set within 8 hours

- Two descriptions agree in Cambridge murder probe by Ed Corsetti and Joe Giulitotti, Boston Record American 14 Feb 1969

- Break is seen in Cambridge murder case, AP via Worcester Telegram, 14 Feb 1969

- Prints found, may be widow’s slayer, Boston Record American, 16 Feb 1969

- Girls’ photos checked in Cape horror by Tom Berube, Ed Corsetti and Joe Giuliotti, Boston Record American, 08 Mar 1969

- Similarities Seen In 2 Cambridge Murder Cases by Richard A. Powers, The Boston Globe, 06 April 1969

- Details on suspects

- Records in 1969 Killing Elusive, The Boston Globe, 18 June 2017

- Mention that Bean case was never solved

- Officials Believe They Have ID’d Killer in 1969 Cold Case, The Boston Globe, 21 November 2018

- “Prosecutors said they have no reason to think Sumpter was responsible for the death of Ada Bean

- Educating Women for Self-Reliance and Economic Opportunity: The Strategic Entrepreneurialism of the Katharine Gibbs Schools, 1911–1968