In the early morning hours of April 10, 1836, the madam of a New York City brothel awoke to someone knocking loudly on the door of her building located at 41 Thomas Street. When she rose to let the visitor inside, she noticed a lamp out of place in the parlor. She carried it up the stairs to return it to its rightful place, only to find one of the girl’s bedrooms filled with smoke and flames.

The madam sent for the watchman as she and the girls doused the fire with water. As the flames died down, there they found 22-year old Helen Jewett, dead on her mattress, but it was clear that Helen’s death was not caused by the fire they’d just extinguished.

Helen, who was born and raised in Maine, was considered a well-known sex worker and a prominent New Yorker, and her case became known around the world. And though Helen Jewett’s case was sensationalized by the press and the tabloid papers of the day, the coverage helped to put a human face on sex work and the criminalized act of prostitution.

As the taboo subject of sex entered the prudish public sphere of the 1800s, it invited commentary, opinion and bias, even among those tasked with the pursuit of justice on Helen Jewett’s behalf.

Helen Jewett’s Early Life

Helen Jewett was born Dorcas Doyen on October 18, 1813, in Temple, Maine, to John and Sally Doyen. Dorcas would change her name often as she moved through life, and, according to Patricia Cline Cohen, author of The Murder of Helen Jewett, “as soon as she could, Dorcas abandoned the name her parents had given her, later insisting that Maria Benson was her natal name.”

I will refer to her as Helen, as that was her most commonly known name. According to the Kennebec Journal, the moniker was one she assumed in honor of her favorite historical character, Helen of Troy.

Helen’s mother died sometime between 1820 and 1823. Her father later remarried and by 1826, 13-year old Helen moved out, or was sent out, and was under the care of the Weston family of Augusta, Maine. The Weston household was headed by Chief Justice Nathan Weston, and he had agreed to take Helen in as a servant.

Helen stayed with the family for five years, and they helped her get an education. That is until Judge Weston discovered that she’d had sex with a local banker when she was just sixteen. Judge Weston and his family were publicly known to be moral and virtuous, and this news implied that they could not properly supervise Helen. Having brought shame upon herself and the household, Judge Weston told Helen to leave.

Sources say that Helen was still a child when she began accepting money for sex. Whether or not this was a choice of her own or one that was made for her is unknown, but let me be clear here – a child being paid for sex is not a sex worker; it’s child rape. In the 1800s, when consent and age weren’t discussed or considered like they are now, she was considered a “prostitute”, a term that is now used to describe the criminalized act of accepting money for sex. I will be using the term sex worker, except where quoting original source material is necessary.

Helen moved through various cities in New England, among them Boston and Portland, renaming herself often, using aliases like Maria Benson, Maria Stanley, Helen Mar, and Ellen Jewett, a name that many newspaper reports would later mistakenly use.

In 1832, at the age of nineteen, Helen Jewett moved to New York City to become what many 19th-century people referred to as “a girl about town,” according to Patricia Cline Cohen. She was well-read, enjoyed philosophy texts and loved to write. And, a repeated fact in every piece about her, Helen was beautiful.

Helen lived in a boarding house at 41 Thomas Street operated by Madame Rosina Townsend. It was a known brothel, and Helen saw men at the house. It was here in New York City, at the Thomas Street brothel, that Helen met a young man she knew as Frank Rivers, but whose legal name was Richard P. Robinson.

Robinson was born in Connecticut to a wealthy family. Patricia Cline Cohen writes that Robinson was the first son but the eighth child; he eventually became one of twelve siblings. He moved to New York City at the age of nineteen and began clerking for a man named Joseph Hoxie.

Richard P. Robinson went by the name Frank Rivers, at least when he was patronizing the Thomas Street brothel. Helen was not the only woman at the brothel with whom he visited; Robinson had earlier visited with another woman named Maria Stevens. According to an 1855 article by The Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Robinson had been familiar with Maria, quote, “before he became attached to Helen.”

The Night of April 9, 1836

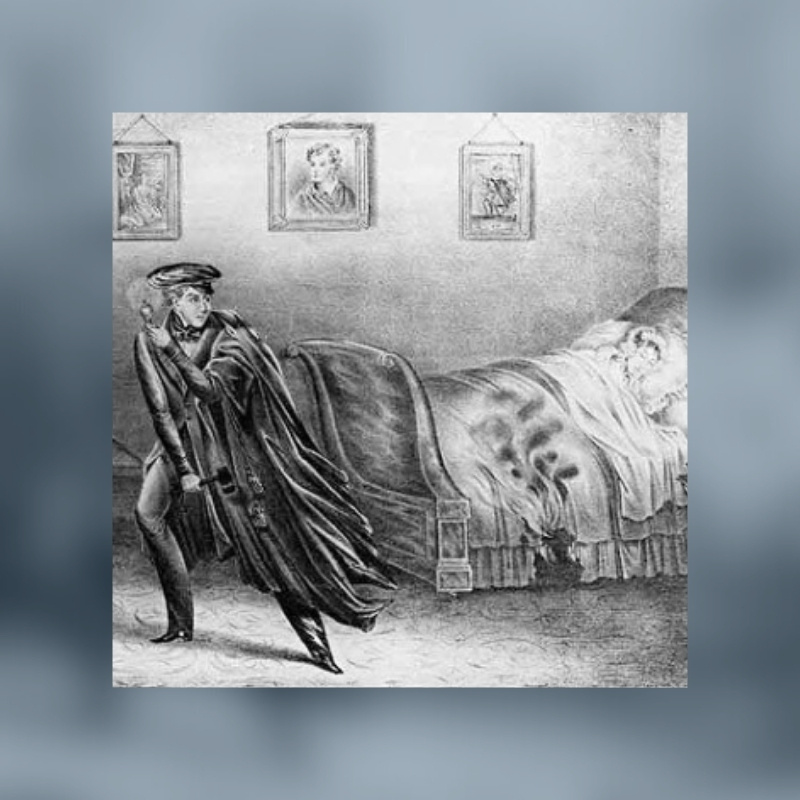

As reported in The Long-Island Star, a young man called upon the Thomas Street brothel to see Helen Jewett on the evening of April 9, 1836. Madame of the house, Rosina Townsend, answered the door around 9 p.m. to find a man wearing a cloak pulled up to his face. Rosina asked the man twice to announce himself, but both times he responded saying only, “I wish to see Miss Jewett.”

Patricia Cline Cohen wrote that Helen may have been expecting two visitors that evening – a man named Bill Easy and a regular visitor who Helen knew as Frank Rivers. Helen had asked Rosina Townsend to decline the visit from Bill Easy but to allow Frank Rivers inside.

Rosina didn’t think the voice sounded like Bill Easy, but she couldn’t be certain it was the voice of the man she knew as Frank Rivers. But when she opened the door and the man’s face was illuminated by the light inside the house, she was confident it was Frank Rivers, so she let him inside.

Frank made his way upstairs to Helen’s room, while Rosina went to find Helen in the parlor to let her know she had a guest. As Helen climbed the stairs to join the man, Rosina heard her say, “My dear Frank, how glad I am to see you.”

Rosina saw the man once more that night, when she delivered champagne to Helen’s room around 11 p.m. According to The Evening Post, he was lounging in bed and reading a paper by the light of a glass lamp near the bed. Helen offered Rosina a glass of champagne, but Rosina declined and retired to bed.

Around 3 a.m. on April 10, 1836, another knock on the front door of the house woke Rosina up. As she walked through the house to the entrance, she noticed that a lamp, still burning, was sitting on a table in the parlor. It didn’t belong there. She also saw that the back door of the house was open. Rosina called out to see who was knocking on the door, but there was no answer.

Rosina shut and barred the back door and picked up the misplaced glass lamp, making her way upstairs to return it to one of the bedrooms. The first room she tried was locked. The next room belonged to Helen Jewett. Rosina turned the handle, pushed the door in, and out came billows of smoke.

After the initial chaos to wake everyone in the house and get them to safety, Rosina yelled to a watchman stationed nearby. As he made his way to the house, Rosina and another woman ran into Helen’s room to save her from the fire. Instead, they discovered that Helen was already dead.

Patricia Cline Cohen writes that what they found, “sent them out of the room in horror. The bed was smoldering rather than blazing. Helen was dead. Three bloody gashes marked her brow, and blood had pooled on the pillow beneath her body.”

Helen’s overnight guest, Frank Rivers, was nowhere to be found.

Episode Source Material

- The Murder of Helen Jewett: The Life and Death of a prostitute in Nineteenth-Century New York by Patricia Cline Cohen

- A history of prostitution in New York City from the American Revolution to the Bad Old Days of the 1970s and 1980s by Stuart Marques, NYC Department of Records and Information Services, 30 Aug 2019

- Robinson, Richard P. by Linda Cheves Nicklas, Texas State Historical Association, 01 Jun 1995

- Murder and arson, The Long-Island Star, 11 Apr 1836

- Trial of Richard P. Robinson, The Evening Post, 04 Jun 1836

- Fourth day, The Evening Post, 07 Jun 1836

- Court of Sessions, The Evening Post, 11 Jul 1836

- Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, 18 Oct 1836

- Suspension of specie payments by the banks, New York Daily Herald, 09 May 1837

- Another female murdered, New York Daily Herald, 20 Sep 1837

- Robinson alive yet, Brooklyn Evening Star, 05 May 1843

- The Evening Post, 08 Oct 1850

- Richard P. Robinson, Kenosha Democrat, 29 May 1852

- Richard P. Robinson death notice, Poughkeepsie Journal, 18 Aug 1855

- Richard P. Robinson, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 21 Aug 1855

- The murderer of Helen Jewett, The New York Times, 22 Aug 1855

- The murder of Helen Jewett, Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, 01, Sep 1855

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 30 Nov 1869

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 14 Aug 1871

- June in law, Democrat and Chronicle, 19 Jun 1875

- The celebrated cases of this city, The New York Times, 15 Jun 1879

- The murder of Helen Jewett, The Port Chester Journal, 30 Sep 1886

- Two incidents that revive a romance, the Shreveport Journal, 28 Nov 1904

- The Murder of Helen Jewett by Cornell University, YouTube, 13 Feb 2014

- Their Sisters’ Keepers Prostitution in New York City, 1830-1870 Marilynn Wood Hill

- Underreporting of Violence to Police among Women Sex Workers in Canada: Amplified Inequities for Im/migrant and In-Call Workers Prior to and Following End-Demand Legislation Volume 22/2, December 2020, pp 257 – 270

- Extraordinary life story of August girl of a century ago topic of Kiwanis address, Kennebec Journal

- The Murder of the Girl in Green One Hundred Years Ago by Sam E. Connor, Lewiston Journal