In April 1979, the lives of two teenagers from two very different parts of the country were inextricably linked by murder. In Brewer, Maine, 17-year old Amy Banks awoke one night to learn that her father, Dr. Ronald Banks, had been murdered in New Orleans, Louisiana.

One month later, authorities in New Orleans arrested 16-year old Isaac Knapper and charged him with the killing of Amy’s father. But Isaac didn’t commit the murder.

This is the story of a wrongful conviction, a young Black man railroaded by the justice system, and evidence withheld at trial that would’ve saved him from a life sentence behind bars in the nation’s bloodiest prison.

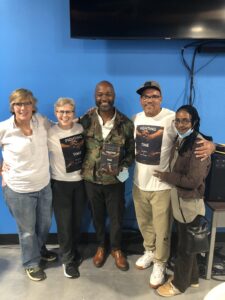

This is the case of Dr. Ronald Banks, told by his daughter Amy Banks, and Isaac Knapper, the man once charged and convicted of his murder.

Meet Amy and Isaac

In 1979, Amy Banks lived with her younger sister and parents in a split-level home in Brewer, Maine. Her older siblings were out of the house and off to college, and 17-year old Amy wasn’t far behind. All of the Banks’ children were raised in an environment that emphasized education – their mother had worked as a teacher and their father, Dr. Ronald Banks, was a celebrated professor of history at the University of Maine’s flagship campus in Orono.

Amy told me she was a decent student, but athletics were the focus of her world at that time.

“I mean my entire life revolved around sports, you know, so it was field hockey in the fall and basketball in the winter and softball in the spring. Twenty-four hours a day I’m at the gym. That’s what mattered to me,” she explained.

Brewer, Maine lies along the Penobscot River just east of Bangor. Mainers from Portland and south of there might be quick to classify this area as Northern Maine, but you’ve still got 200 miles or so before you hit the Northernmost point of the Pine Tree State. With the population of just under 10,000 residents, it is a smaller community, a third of the size of its sister city Bangor. Brewer’s population as of the 2020 census was 97% white, about 7% higher than Maine as a whole.

“I grew up in Maine. Maine is white. Maine is whiter than white. And so another part of it was that I didn’t have the opportunity to be interacting with a lot of people that were different,” Amy continued, “Pretty much everybody that went to school with me looked like me. I would say around like race relations, we were kind of naive. We really didn’t have to think about it.”

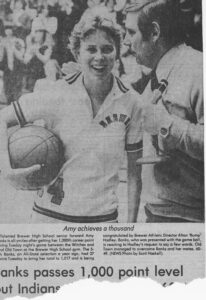

Amy wrote in Fighting Time that during the spring of 1979 she was working towards her goal of making the All-State Basketball team. Two hundred jump shots each day, no matter the conditions. She was disciplined and focused. Amy’s goal felt like a reality, too, with a local paper sending a photographer to her house. No promises she was on the team, but the photoshoot seemed like a sign.

Meanwhile, in a parallel timeline nearly 1800 miles south of Maine, another teenager was navigating a life that revolved around sports, but in the very different setting of New Orleans, Louisiana, a population that is 59% Black, according to the 2020 census.

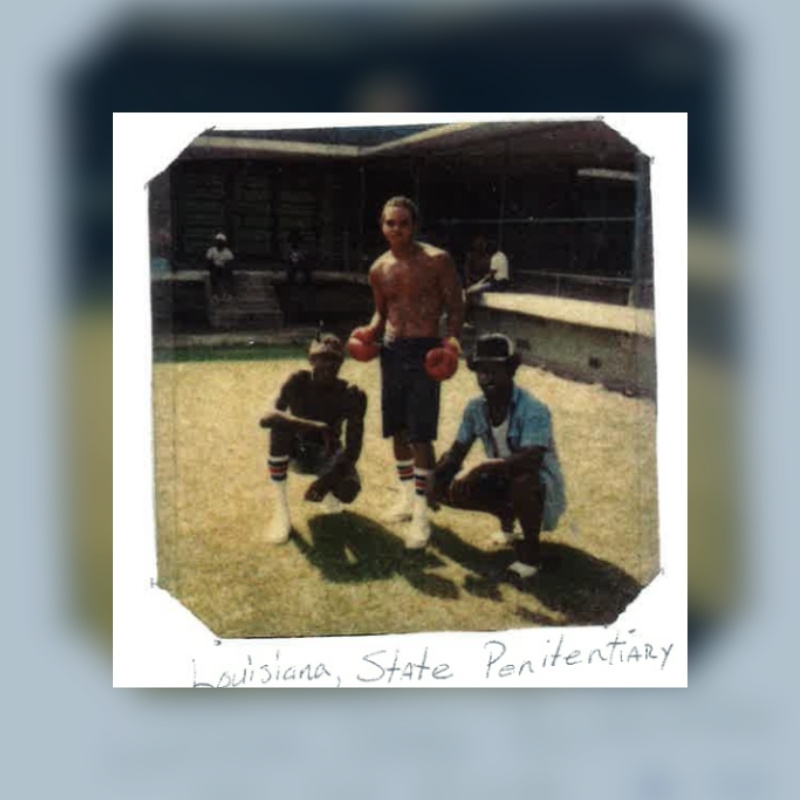

At the time, 16-year old Isaac Knapper was emerging as a stand-out athlete.

“I loved sports. I loved football. In fact, I was a boxer and people asked me all the time, ‘what was your favorite boxing or football?’ And I always say football was my favorite,” Isaac began.

“When I was a kid, I would have my boxing gloves in this hand and I would have my football helmet in his hand and I would go to football practice and I’d leave football practice and I’ll be rushing. I had to run to the gym, ‘cause Percy didn’t want us riding to the gym. He wanted us to jog to the gym. And so I would leave football practice and just run straight so I could make it to the gym on time for boxing,” Isaac laughed, “My mom used to tell me, she said, ‘you have to decide which one of these sports you’re going to go and do because you can’t, you’re killing yourself. You trying to run from one to the other, you know, every day, it’s just, you just can’t do that.’”

His mom’s name is Clara, and after hearing Isaac speak about his mother over the course of our time together, I wish now that she could have joined us for this conversation. She is a constant presence and guiding light in his life. It’s clear in the way he speaks about her that she instilled the values of hard work, humility, and most of all, heart, into the man Isaac is today.

“My mother raised me to be humble,” Isaac explained, “Along with two brothers and seven sisters, and we was more or less fatherless. My father was never around and we grew up in poverty, living in the projects and with a single parent that worked. And my mother lived in the projects but she’d never been on welfare and I never could understand that, but she worked and she didn’t believe in taking a handout.”

Isaac continued, “She always wanted to work and work and work and that’s what she did, and that kind of motivated me to push myself.”

“I really appreciate my mom,” Isaac told me, “She’s my number one fan. She’s my hero, and watching her go through the struggles that she was going through to try and raise ten kids alone, that was real tough. And I wanted to be somebody that could help my mom to ease some of that pressure. She took care of us and she made sure that we didn’t have everything we wanted, but we had everything we needed to survive and to become who we are today.”

Dr. Ronald Banks

As for Amy’s parents, they were both born and raised in the coastal town of Camden, Maine. Her father, Dr. Ronald Banks had a few things in common with Isaac himself.

“One of the things that comes to mind when I think about my dad is humble. It’s probably why I resonate so much with Isaac. He was a very humble guy. He himself was fatherless. He had been born and raised by a single mom. I think for him, education really kind of allowed him to move to a different place in life,” Amy shared.

She continued, “He’s a very smart guy, very dry sense of humor.”

Dr. Banks studied at the University of Maine, earning both his Masters and Ph.D. there before becoming a professor of history at UMaine himself. The UMaine student newspaper, The Maine Campus, wrote that Dr. Banks was perhaps best known for his book A History of Maine among other books and scholarly publications. Then-Governor Joseph E. Brennan of Maine recognized Dr. Banks as one of the leading historians of Maine, while his colleagues described him as much-loved.

At home, Ronald was a helpful partner to his wife, not minding “traditional gender roles” of the era, assisting with the laundry and the cleaning and the cooking.

Amy was wonderfully honest with me when I asked about her relationship with her father. I say wonderfully, because it was relatable.

“God, the memories that I have of him,” she paused for just a moment, “Some of them are complicated. We didn’t have a perfect relationship by any stretch.”

“Where we connected was very much around sports beause he was also an athlete. He was a two sport athlete at Camden High and kind of good at a lot of things, President of his class and used to tell stories of being scouted for the Boston Red Sox. It was obvious that he took a real pleasure and interest in that. I was the person that was most interested in sports in our family. We had a real bond with that.”

April 12, 1979

April 12, 1979 would’ve been like any other day for Amy Banks, though her father had left that morning for a conference with a colleague in New Orleans, Louisiana. Amy was at home in Brewer, Maine, preparing for what she anticipated would be good news about the All-State Basketball team roster. In Fighting Time, Amy described the plan she had with her father to get the news about the team as soon as possible. She went to bed that night only for the plan, and her life, to be altered in an instant.

“I was woken up probably around 11, 11:30 with just the worst screaming I’ve ever heard in my life.”

Amy was pulled from her bed by the sounds of her mother in clear distress, in pain. As she rounded the split staircase to the main level of their home, a family friend met her face to face.

“She came down and literally just looked right at me and said, ‘There’s been an accident. Your father has been shot.’ Nobody, I think at that point had any real details of what had happened,” Amy told me.

Dr. Ronald Banks had been shot and killed just steps from his hotel in New Orleans, the victim of an attempted mugging turned deadly.

Dr. Banks and his colleague, John Hakola, checked into the Hyatt Regency just a few blocks from The French Quarter in New Orleans. Also just a few blocks away were the Guste housing projects, an area described by Amy in Fighting Time as notoriously violent – a detail withheld from the guests who booked their rooms at the Hyatt blissfully unaware of the danger in the area.

Ronald and John were walking back to the hotel when they were confronted by two young men. The boys demanded money from the pair. Dr. Banks had just enough time to utter the words, quote, “You’ve got to be kidding me,” before one single gunshot fired into his face claimed his life, right there on a New Orlean’s sidewalk, steps from the safety of his hotel. The assailants fled on foot.

Isaac and Amy’s stories continue on Dark Downeast. Listen now wherever you get your podcasts or tune in via the player above to hear their first hand accounts of the homicide, arrest, conviction, and exoneration that changed both of their lives.