On Monday, May 31, 1971, the quiet of a dark late spring evening in Bangor, Maine was interrupted by frightened screams inside an Otis Street Apartment building. Though several residents would later report hearing the sounds of a woman in distress, no one called for help, no one picked up the phone to dial the police, and no one checked in on their downstairs neighbor, 84-year old Charlotte Dunn, until the next morning when help would be a lost cause.

Police had a prime suspect for Charlotte Dunn’s murder from the very first day of the investigation, but they’d need to pull some crafty police work to secure the hard evidence against him. Crafty, or maybe questionable police work, depending on who you asked at the time.

A rampant rumor mill, contentious evidence, and a slippery suspect made for a complicated investigation as Bangor Police worked jointly with the Maine State Police Homicide division on a case for the very first time. Charlotte Dunn would see justice, but not without a fight.

“Growling Sounds, Like an Animal”

On the night of May 31, 1971, a young mother’s ears picked up an unusual sound. She was accustomed to the whimpers and cries of her infant – she even learned to interpret a hungry cry from a pained or tired one – but the noise she heard wasn’t any of those sounds and they weren’t coming from her baby.

She later described what she heard to Bangor Daily News writer John Day. First she heard screams, with a loud banging. And then, “Low growling sounds, like an animal, or some kind of wild dog.”

The neighbor, identified only by her first name, Ann, thought the noises might be coming from the basement of the building – the old furnace was known to clang and groan as it fired up – but not the screaming. That certainly wasn’t the furnace.

Ann took her tiny baby into her arms and stepped out into the hallway. She told John Day that she noticed the front door of the building was open. As she stood outside the door of a neighboring flat on the first floor, the growling noise grew louder. Her heartbeat rose into her ears. She was suddenly acutely aware of her vulnerability, standing there with her child pressed to her chest, “I guess I panicked. I ran back into my apartment, locked the door and turned off the lights.” She did not call the police.

Ann watched out the window from her pitch black apartment for any sign of an intruder fleeing on foot. Had someone left the Otis Street building and turned left toward State Street, Ann would’ve seen the person, but she didn’t see anything. “Not even a shadow,” she told John Day. Her husband returned home from work 15 minutes later. He didn’t see anyone either.

The next morning, Ann went with her mother and two brothers to take a look in the hallway near the apartment where she had heard the frightening noises the night before. They noticed that the door was scratched with paint flaking off and it was cracked on one side, but still locked.

Ann spoke with other tenants in the building that morning, and several of them reported hearing the noises and screams coming from Charlotte’s apartment, too.

The residents of 11 Otis Street in Bangor, Maine would later tell reporters, “At the time we thought it could have been a fight between a man and his wife. We were not sure whether the noise came from upstairs or from the [Dunn] apartment.” And still, nobody called for help.

By 11 a.m. the next morning, the whole building learned the source of those sounds. Their neighbor Charlotte Dunn was dead.

About Charlotte Dunn

83-year old Charlotte A. Dunn is described in nearly every media report at the time as a “spinster”. It’s an outdated and derogatory term for an older unmarried woman. Out of curiosity, I researched the origins of this word. It has roots all the way back to mid-1300s England when unwed women were automatically assigned a lower status by society.

Also in those times, your occupation was often used as a surname – think Smith, Tanner, Baker – and so Spinster was used as a surname on legal documents for people who performed combing, carding, and spinning wool, and those people happened to be unmarried women because the occupation did not require expensive equipment that only husbands could buy their wives.

By the 17th century, according to Merriam-Webster, the term spinster was used on legal documents to describe unmarried women, regardless of their actual occupation.

But let me emphasize, the use of the term “spinster” to describe Charlotte Dunn is not only degrading, it completely dismisses her vibrant life of service, her dedication to her extended family and her apparent entrepreneurial spirit.

Charlotte was born and raised in the Bangor-Brewer area and spent most of her life there. Charlotte had no children of her own, but she was close and very involved with her nieces and nephews, and her grandnieces and grandnephews.

She had most recently worked at St. John’s Parish Rectory as a cook and was a member of the St. John’s Parish Council of Catholic Women. Before that, Charlotte and her sister Sarah were cooks for former Massachusetts Senator Leverett Saltonstall and former governor of the same state. In the 30s, just before World War II, Charlotte and Sarah operated a tea room together in Bar Harbor.

Though it appeared Charlotte was slowing down her professional endeavors as an octogenarian, she supported and volunteered many local charities close to her heart. She was still active with her church, attending mass several times a week.

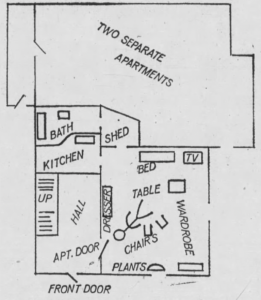

Charlotte lived just a half mile from that church in an apartment at 11 Otis Street in Bangor. The building had 12 flats, and hers was made up of one open room furnished with a bed and television, a dresser and wardrobe, two chairs, a table, and some houseplants, with a small shared bathroom and kitchen.

Your home should be your safe space – comfort and security are requisite. But for the last year of her 16 years on Otis Street, Charlotte Dunn lived in fear in her own home.

Attack and Peeping Tom

On April 24, 1970, a man stood in the hallway just outside Charlotte Dunn’s apartment. Without a word, he pushed Charlotte back into her apartment and exposed himself. According to reporting by John Day for the Bangor Daily News, Charlotte ran from the man, escaping into an adjacent apartment that shared a bathroom with hers. Her neighbor scared off the man before he could cause any further harm.

Charlotte called the police and reported the attack, giving the best description she could, though her memory was clouded by fear. All she could tell them is that he was young, perhaps 30-years old, with a medium build and dark hair.

After that, Charlotte reported up to 10 occasions of a peeping tom lingering outside her windows and creeping around the building. Each time she reported it to Bangor police, they’d come check it out but found nothing. Patrolman William Collins, who happened to be Charlotte’s nephew, told the BDN, “I began to think maybe it was all in her mind. The boys came up here but there was no indication of anything.”

But Charlotte wasn’t the only person reporting a man prowling around and exposing himself to people in the East Side of Bangor in late 1970 and early 1971. A man matching the description of Charlotte’s attacker had also exposed himself to other women and even children in the neighborhood. Because the description was so general, police told the Bangor Daily News, they couldn’t be sure if there was one or many culprits.

Police also noted that in two of the attacks, witnesses said the man took off in a blue and white Chevrolet station wagon. In two other incidents, the man drove a pick-up truck. In at least one of the reports, the man fled in his car down Otis Street after exposing himself to two junior high school students.

Ever since that first night when the man accosted her in the hallway, Charlotte was extremely cautious about answering the door, especially since no culprit was ever apprehended for that incident or the many others. But a neighbor later told the Bangor Daily News that despite her caution and fear, Charlotte knew only kindness.

“[She was] one of the nicest women you could ever meet,” said a tenant of the 11 Otis Street apartment building, “So nice that she might open her door to somebody who gave her a convincing story.”

That same neighbor also said that Charlotte routinely shut off the hallway light just outside her apartment door at 11 p.m. every night. That was around the same time neighbors reported hearing screams on May 31st, 1971.

May 31, 1971

On Monday morning, Memorial Day, May 31st, 1971, Charlotte attended mass at St. John’s Catholic Church at 9:30 am, and then visited a family plot at the adjoining cemetery.

Although it was a holiday that day and Charlotte’s day didn’t appear to hold much more than her morning activities at church, the rest of her week was shaping up to be quite busy. She planned to attend her grand-niece’s wedding in Houlton the coming weekend, and had bought a new dress and made an appointment at the beauty parlor to get her hair freshened up the following morning for the occasion.

But when her 10 o’clock appointment on Tuesday, June 1, 1971 rolled around, Charlotte didn’t show up. A chain of telephone calls began to check in on her.

The wife of Charlotte’s grandnephew called her sister, who had a key to the Otis Street building where Charlotte lived. That sister gave the key to her daughter Mary Lou, and her son-in-law, William Armes, and asked them to go see if Charlotte was home.

According to the Bangor Daily News, Charlotte’s apartment was locked when William and Mary Lou arrived at Otis Street. Her morning newspaper was still sitting outside the door. William and Mary Lou knocked several times, but there was no response from inside the apartment. They were immediately struck with worry that perhaps Charlotte had suffered some sort of medical event, maybe a heart attack, so William began ramming the door with his shoulder until it crashed open.

That’s when William saw Charlotte laying lifeless on the floor in her night clothes. He turned to his mother-in-law, “Don’t look,” he told her, slamming the door on what he just saw. William yelled into the hallway for someone to call the police.

The Investigation

Bangor Police found Charlotte Dunn laying on her back, her head just inches from the door of her apartment, with her legs and arms outstretched. Her apartment was relatively undisturbed, except for the two dining chairs that were pushed out of place from their usual spot at the table and a broken candle laying on the ground.

Evidence technicians collected a number of items and photographed Charlotte Dunn’s apartment, as well as dusted for fingerprints on the door and surfaces inside the apartment. They collected fingernail scrapings and paint chips found underneath Charlotte’s body.

The evidence would be processed in the state police crime lab in Augusta. Meanwhile, pathologist Dr. Rudolf Eyerer performed the autopsy and found Charlotte’s cause of death to be strangulation. Further testing was scheduled to determine if Charlotte had been sexually assaulted.

Who would kill an 83-year old woman? And why? Authorities considered a motive in the case, theorizing at first it was a robbery turned deadly. According to reporting by John Day for the Bangor Daily News, Charlotte Dunn used to collect the rent payments from the other tenants in the building at the end of the month, but she hadn’t done that in nearly two years. Besides, there was another more obvious path the investigation could follow – the man who had attacked Charlotte a year earlier and her numerous reports of a young, dark haired prowler.

Did that man, the one that authorities could never find, come back to find her, his indecent exposure escalating to murder?

On the first day of the investigation, police questioned several men about the killing, including men with histories of sexual offenses. According to the Bangor Daily News, one of the men questioned was also previously charged with beating an elderly woman. When police pulled him in for an interview about Charlotte Dunn, they noted several visible scratches on his body. This man and the others brought in for questioning, however, were not named or labeled as suspects in public reports.

Investigators believed that fingerprints collected at the scene would ultimately narrow down the suspect pool. Two State troopers were tasked with the painstaking fingerprint analysis process, comparing prints lifted at the scene of Charlotte’s murder with fingerprints on file from previously convicted criminals, with priority on those who had been convicted of high and aggravated assault and battery. Other evidence and prints were sent to the FBI laboratories in Washington for additional analysis.

While the prints were processed and authorities hoped for a match, the residents of Bangor took precautions to protect themselves in the meantime.

Episode Source Material

- STATE of Maine v. Robert P. INMAN. 301 A.2d 348 (1973)

- STATE of Maine v. Robert P. INMAN. 350 A.2d 582 (1976)

- Obituary for CHARLOTTE A. HARRIS DUNN

- Woman, 83, strangled here by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 02 Jun 1971

- Screams heard, went unreported by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 02 Jun 1971

- ‘Growling…Like an animal’ by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 02 Jun 1971

- Screams go unheeded by neighbors, AP/Biddeford-Saco Journal, 02 Jun 1971

- Evidence analyzed in strangling, Bangor Daily News, 03 Jun 1971

- Bangor murder fans demand for security by David Bright, Bangor Daily News, 03 Jun 1971

- Deviate sought in slaying by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 04 Jun 1971

- Fingerprints may give clue in death probe by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 04 Jun 1971

- Police Beat: Perhaps it was ants in his pants! Bangor Daily News, 04 Jun 1971

- Fingerprints key in strange case by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 04 Jun 1971

- FBI analyzes some evidence involving strangle case here, Bangor Daily News, 06 Jun 1971

- Still no lead in death probe, Bangor Daily News, 06 Jun 1971

- Police to map future strategy in murder case, Bangor Daily News, 08 Jun 1971

- Specialist squad to work full-time on Dunn murder by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 10 Jun 1971

- Offer reward in killing of Bangor woman, Bangor Daily News, 11 Jun 1971

- ESP expert declares same man responsible for the Bangor House and Dunn Stranglings by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 17 Jun 1971

- Murder rumors untrue, say police by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 23 Jun 1971

- Otis street area screams investigated, Bangor Daily News, 30 Jun 1971

- Omission of LaBree in Dunn murder probe is explained by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 15 July 1971

- SHC worker will enter plea today, AP/Biddeford-Saco Journal, 22 Jul 1971

- Robert P. Inman of Holden charged in Miss Dunn’s strangulation death by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 22 Jul 1971

- Holden man chief suspect from start in Dunn murder by John Day, Bangor Daily News, 22 Jul 1971

- Murder case suspect held without bail, Bangor Daily News, 23 Jul 1971

- Stern named co-counsel in Dunn case, Bangor Daily News, 29 Jul 1971

- Probable cause is found against Inman, Morning Sentinel, 04 Aug 1971

- Grand jury to get strangle case by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 04 Aug 1971

- Grand jury returns murder indictment, Bangor Daily News, 09 Sep 1971

- Fire damages murder scene, Bangor Daily News, 29 Nov 1971

- Inman trial is expected to be held in February, Bangor Daily News, 16 Dec 1971

- Murder trial slated for new court term, Bangor Daily News, 28 Dec 1971

- Inman to be tried on murder charge, Bangor Daily News, 08 Feb 1971

- Inman trial is postponed, Morning Sentinel, 09 Feb 1972

- Palm print rubs out Inman trial, Bangor Daily News, 09 Feb 1972, page 2

- Supreme court ruling asked on Inman evidence, Evening Express, 09 Feb 1972

- Capture two who walked away from state hospital, Morning Sentinel, 06 Apr 1972

- Inman, on pass, overstays leave by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 06 Apr 1972

- State hospital ends criminal-pass policy by Paul Macaulay and David Bright, Bangor Daily News, 07 Apr 1972, page 2

- Psychiatrist quits at state hospital by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 13 Apr 1972, page 2

- Alleged jail break effort by 2 inmates is failure by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 26 Jan 1973

- Inman scheduled for trial following court decision, Bangor Daily News, 07 Feb 1973

- Inman trial slated to begin Monday, Bangor Daily News, 21 Feb 1973

- Inman trial begins today, Bangor Daily News, 26 Feb 1973

- Inman jury selection begins, Bangor Daily News, 27 Feb 1973

- Inman jury visits scene by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 04 Mar 1973, page 2

- Pair tells of finding body by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 05 Mar 1973

- Denial by Inman quoted at trial by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 06 Mar 1973, page 2

- Inman judge okays ‘palm print’ by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 07 Mar 1973, page 2

- State rests case at Inman trial by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 08 Mar 1973, page 2

- Jury finds Inman guilty by Paul Macaulay, Bangor Daily News, 09 Mar 1973

- Inman hears life sentence with poker face, Bangor Daily News, 11 Mar 1973

- Murder conviction is upheld, Sun-Journal, 03 Jan 1976

- Maine court defines rights, Morning Sentinel, 08 Jan 1976

- Suspect question conditions defined, Lewiston Daily Sun, 09 Jan 1976

- East Holden man to get parole hearing on life sentence for killing Bangor woman by A. Jay Higgins, Bangor Daily News, 08 Aug 1981