In April of 1973, the vibrant college town of Orono, Maine was shattered by a shocking murder that sent tremors through the University of Maine community. The victim was Frederic Alan Spencer, a promising UMaine graduate student with a bright future ahead. When Frederic’s roommate came forward and confessed to the killing, it seemed justice would be swiftly served – an open and shut case.

However, as the trial of Richard Westall Rogers Jr. unfolded, it was clear the case was far from simple. Despite his admission of guilt, the proceedings took a surprising turn, leaving many puzzled and questioning the very fabric of the justice system. Nobody in that courtroom could have known at the time, but the unexpected decisions made in the case of Frederic Spencer would set in motion a chilling and deadly ripple effect that only grew with intensity and consequence over the next few decades.

Decades later, the same killer would resurface, leaving a trail of death and despair in his wake. At least two more lives would be lost at the hands of this elusive murderer, with evidence pointing to even more victims attributed to the man who would be labeled the Last Call Killer.

I’m going to tell you Frederic Alan Spencer’s story, as well as the stories of Peter Stickney Anderson, Thomas Mulcahy, Anthony Edward Marrero, and Michael Sakara. Though these cases reach far beyond New England’s six states, it all begins right here in Maine.

Orono, Maine

In 1973, the town of Orono, Maine, was on the verge of celebrating the bicentennial of its original settlement by American colonists. The region of pines at the intersection of the Stillwater River and the Penobscot River was originally occupied by the Penobscot Nation, an Indigenous group native to Maine. Once the land was incorporated in 1806, it was officially given its name after the Chief Joseph Orono of the Penobscot tribe.

Over its long history, the town of Orono has been known by several identities. Its location on the Penobscot River historically positioned Orono as an ideal location for sawmills, as enormous logs from across the northern forests of the state floated south down the river to the mills.

Orono is also the home of the iconic Pat’s Pizza, a local chain that has held its original home on Mill Street since it was founded by C.D. “Pat” Farnsworth in July of 1931. Orono is also, and perhaps best, known as the college town of the University of Maine’s flagship campus.

My alma mater, the University of Maine, UMaine for short, was founded in 1862 and officially established in 1865. Throughout the history of the University of Maine system, Orono has remained the flagship site and primary research university of the state. While the University has seven campuses today with varying degrees and certificates, Orono remains home base. Undergraduate and graduate students come from across the country and the world to learn at UMaine, and the campus is especially attractive for those interested in scientific research due to its location with close proximity to many forests, rivers, and the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1973, Orono was home to nearly 10,000 full-time individuals with the addition of 8,511 University of Maine students during the academic year. The 1973 University of Maine Catalog paints a picture of an academically rigorous and welcoming campus, with the 1973 University of Maine Prism – the campus yearbook – reflecting the energy and life breathed into the towering brick buildings by the students themselves.

In a note in the Prism by Trish Riley, who was President of the UMaine Student Government at the time and remains very involved in the University of Maine System to this day, she characterized her class as a series of “Movements.” The students of this time period were anti-war, hippies, environmentalists, and women’s liberationists. They protested outside the house of the President of the University after the massacre at Kent State in 1970 and held fiercely to dreams and aspirations.

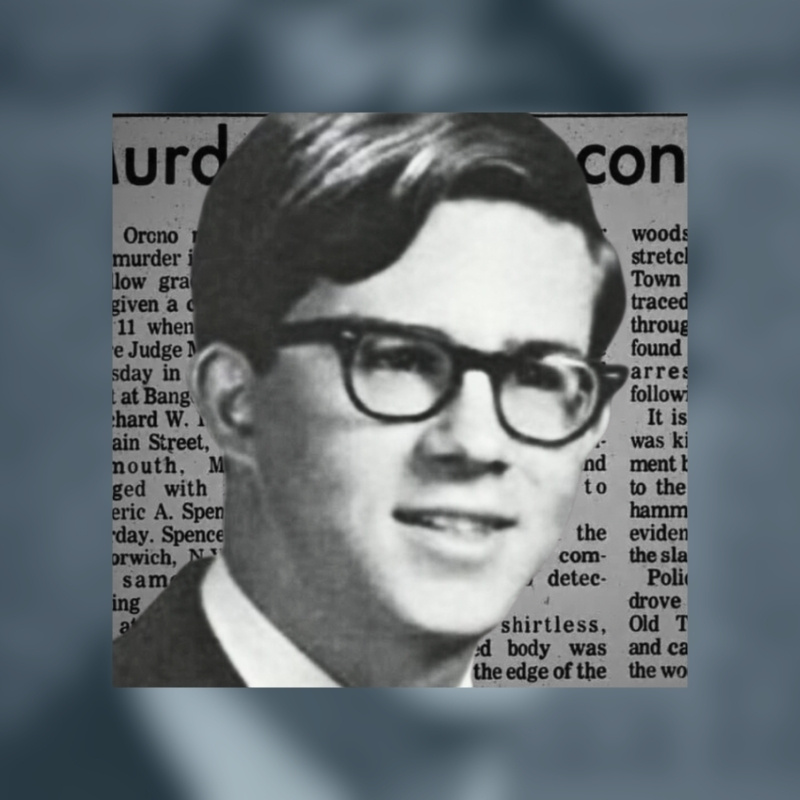

This student body also shared a campus with Frederic Alan Spencer, a graduate research student at the University of Maine in the Department of Entomology.

About Frederic Spencer

As part of the research for this story, we turned to Elon Green’s book “Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York.” This meticulously researched and brilliantly written work served as an incredible resource for learning about the men at the center of these cases with a true victim focus and provided details and information not available in other reporting. The book has now been adapted into an HBO docuseries called Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York, airing now in July and August of 2023. I’ll link both Elon’s book and the series in the show description of this episode. It’s worth a read and watch to learn more about these stories, including the story of born New Englander, Frederic Alan Spencer.

Frederic Spencer was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 13, 1950. His parents, Dr. Claude Spencer and Louise Wible Spencer, had met and fallen in love during their undergraduate tenure at the University of Michigan. Both Claude and Louise had studied chemistry during their time at Michigan, graduating together in 1942 and marrying just two years later in September 1944.

The pair loved the outdoors and the study of science and were both dedicated academics. Their dedication to education was such that the Spencers eventually moved to Boston in order to allow Claude to pursue his Ph.D. in chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was during their time in Boston that the couple had their first child, Frederic.

Frederic was the oldest of three children; after his birth, Claude and Louise had his younger siblings, Karen and Richard. When Frederic was nine years old, the whole family moved to Norwich, New York. Following his graduation from his Ph.D. program, Claude had been hired for a position with the Norwich Pharmacal company, now known as Norwich Pharma Services. While in Norwich, Louise continued her own studies by pursuing a Master’s degree in education and learning disabilities, later pursuing a career in education.

Claude and Louise were devoted parents to their three children and worked hard to raise a close-knit family. Norwich was the ideal location for the Spencers, as the small town offered plenty of opportunity while maintaining the feeling of a supportive community.

During his childhood, Frederic Spencer took advantage of the vast areas of untouched nature surrounding his home. He was a Boy Scout, spending his free time volunteering and spending time outdoors, having learned from his parents to love science and the wilderness.

The Spencer family spent their summers in Vacationland. It was in Maine that Frederic passed the days hiking in the rocky terrain of the state’s mountain ranges, including portions of the Appalachian Trail that took him up thousands of feet in elevation and allowed him to experience the smell of pine trees and the joy of lakes and hidden wild blueberry patches that can only be found in the summer in Maine.

At home in Norwich, Frederic created a community for himself as well. Throughout high school, he maintained a relationship with a young woman named Jenny Riley. Though the pair grew apart as they each pursued their dreams at separate colleges, she remained close to the family for years.

In addition to his strong relationships with his family and friends, Frederic was very academically accomplished. On October 24, 1967, the Press and Sun-Bulletin of Binghamton, New York announced that “nine Norwich Senior High School students have received letters of commendations honoring them for their high performance on the 1967 National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test.” One of these students was “Frederic A. Spencer, son of Mr. and Mrs. Claude Spencer.”

Just a few months later on February 14, 1968, the same paper shared that Frederic held one of the top five scores in Chenango County of a qualifying test he had taken in October of 1967. This accomplishment meant that Spencer would receive the Regents scholarship, which made students “eligible to receive an annual award of $250 to $1,000, depending on family income, while attending any college in the state approved by the Board of Regents for this purpose.” These announcements showcase the passion and dedication that Frederic displayed for his learning even as a high school student.

These accomplishments became even more apparent when Frederic left New York for his undergraduate studies. Like his parents, he pursued a science degree at the University of Michigan, graduating exactly thirty years after them in the spring of 1972.

While many undergraduate students struggle to decide what path to pursue as their graduation day approaches, Frederic did not. As a senior in college, he was recruited as a graduate student to the Department of Entomology at the University of Maine by Professor David E. Leonard. Frederic’s interest in entomology, the study of zoology and insects, intersected perfectly with this opportunity. Plus, it offered Frederic the opportunity to return to Maine, the state where he had spent all those summers during his youth and where he had fallen even more deeply in love with science and the surrounding outdoors.

By the fall of 1972, Frederic had officially moved to Orono, Maine. He established his new life as a resident of 10 Main Street, a duplex just a mile off campus. Though it was not officially a dormitory, this house was frequently rented during the academic year as a home to students at the University of Maine. As a graduate student, Frederic opted to live with two roommates, who were both affiliated with the University as well. Their names were William Mazerolle and Richard Rogers.

William Mazerolle would later share with Maine police officers that the three roommates were never close to one another during that year of living together. He noted that Rogers and Spencer were not friendly and often got into small arguments with one another. However, he never witnessed the pair display any outward anger or violence towards each other. But after less than nine months in Orono, the life of Frederic Spencer would come to an end at the hands of that same roommate.

The Murder of Frederic Spencer

According to the Press and Sun-Bulletin, the same publication that had shared Frederic Spencer’s many academic accomplishments just five years before, two bicyclists out for a ride in neighboring Old Town on April 30, 1973, discovered the body of a man wrapped in “a tent-like material.” Once the cyclists realized what they had found, they contacted the police immediately.

Investigation of the site revealed that the man had been dead for less than two days. He had sustained significant blunt force trauma to the back of his head, and had eight lacerations on his skull, damaging him permanently and nearly ending his life. The act that ultimately caused his death was strangulation with a plastic bag. His body was dumped off a lonely road at the edge of a pine tree forest.

Many years later, David E. Leonard, who had been Frederic Spencer’s academic advisor, said in the Bangor Daily News, “I had the unpleasant task of identifying Fred’s body, with his face so battered by his confessed slayer that recognizing him was both nauseous and difficult.”

Though investigators were unable to find any forms of identification with the body, they did find a key. The key was tied to a post office box in Orono belonging to Frederic Spencer and eventually led police back to 10 Main Street, ten miles away from where Frederic’s body had been found.

When law enforcement knocked on the front door, William Mazerolle answered. He told police that he did not know where either of his roommates were at the moment. He had not seen Frederic in a couple of days, but their schedules did not always align, and this was not unusual. Nevertheless, Mazerolle welcomed police into the home to look around for evidence of what may have happened to Frederic.

Everything about the duplex appeared normal at first. As police officers made their way through the building, they did not notice any items overturned or anything out of place. However, this all changed when they reached the bedroom of Richard Rogers.

When they opened the door to the room, they found blood everywhere. There were bloody fingerprints and footprints on the door of the room and across the floor, and droplets of blood splattered across the walls. There was also a blood-stained hammer sitting in plain sight in the room. This hammer was soon identified as the murder weapon.

Frederic Spencer did not have any enemies or anyone who disliked him, as far as his roommate or friends were aware. Because of the significant amount of evidence in the duplex that Frederic had shared with his roommate, there was never any suspect other than Richard Rogers.

Police met Richard Rogers as soon as he walked through the door of 10 Main Street. He was immediately taken to the police station to be interrogated. Investigators drilled him about his whereabouts on Saturday night and his relationship with his roommates. It didn’t take long for the truth to out. Richard Rogers confessed to killing Frederic Alan Spencer. His is the only version of events we have of that night in April of 1973.

According to Richard, he returned home on Saturday, April 28, 1973, and walked to his room. When he opened his door, Rogers claimed that he found Spencer standing near his dresser. Some accounts note that Frederic was looking through the room and rifling through Richard’s possessions.

Either way, Richard stated that Frederic had turned towards him once he had opened the door and attacked him with a hammer. In self-defense he claimed, Richard wrestled the hammer from Frederic and struck him repeatedly in the head, then suffocated him with a plastic bag.

Rumors suggested that there was more to the attack. According to “Last Call,” some speculated that Spencer might have “come on” to Rogers. While this argument was never officially utilized in court, the so-called “gay panic defense” – the idea that a heterosexual individual is justified in hurting or killing a member of the LGBTQ+ community because they panicked and lost control – was not uncommon in this time period and is still used in some states today, though it is now prohibited in Maine.

Richard Rogers was arrested and placed in the jail where he would spend the next six months. His intake was careful and conscientious. Orono police meticulously gathered information from Richard Rogers. They took note of his height and weight and were sure to catalog all ten of his fingerprints, completing his profile in Penobscot County criminal records.

Episode Source Material

- Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York by Elon Green

- Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York on HBO

- Associated Press. “3 Counties’ Scholarship Winners.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 14 February 1968.

- Associated Press. “Arraignment Held in Murder Case.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 4 May 1973.

- Associated Press. “Body found along Pike.” The Evening Sun. 23 January 1992.

- Associated Press. “Dismembered body identified as Massachusetts sales executive.” UPI Archives. 13 July 1992.

- Associated Press. “‘Evil’ ex-Mainer gets consecutive life terms.” Sun Journal. 28 January 2006.

- Associated Press. “Mounties help ID prints in gay killings.” The Bangor Daily News. 1 June 2001.

- Associated Press. “Pa. crime up 4.1%.” Philadelphia Daily News. 9 August 1991.

- Associated Press. “Pattern in a Trail of Death.” Hartford Courant, 1 June 2001.

- Associated Press. “Police: Serial killer may stalk gay men.” News-Journal. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Police suspect killer stalking gays.” The Berkshire Eagle. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Serial killer may have slain 4 gay men, authorities say.” The Akron Beacon Journal. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Socialite found dead in trash can was ‘a lost soul.’” The Philadelphia Inquirer. 10 June 1991.

- Associated Press. “Student is found innocent in Orono beating death.” Daily Kennebec Journal. 5 November 1973.

- Associated Press. “Student’s Trial This Fall.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 1 October 1973.

- Associated Press. “Technology May Provide Link to Suspected Serial Killer.” Hartford Courant, 2 June 2001.

- Bennett, Troy R.; Degre, Gabor; Feulner, Brian; Harrison, Judy; McCrea, Nick; Moretti, Mario. “Charlie: Thirty years after the killing of a young gay man shocked Bangor, his death is now remembered for its profound effect on Maine.” The Bangor Daily News. June 2014.

- Burnham, Emily. “Charlie Howard murder dramatized in ‘It’ sequel.” Foster’s Daily Democrat. 4 September 2019.

- Cave, Damien. “As Killer Faces Sentencing, His Motive Remains Elusive.” The New York Times. 27 January 2006.

- Choice. “What Happened To New York: A History Of The 00’s So Far.” Gawker. 31 December 2007.

- Clinton, Roger. “2nd body found at turnpike.” Intelligencer Journal. 22 January 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Friends, family gather to mourn Sudbury man.” The Boston Globe. 17 July 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Police recover belongings of slain Sudbury man.” The Boston Globe. 15 July 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Police seeking motives in dismemberment.” The Boston Globe. 17 July 1992.

- Curran, John. “Former Maine man gets consecutive life sentences.” Foster’s Daily Democrat. 27 January 2006.

- Dawson, Mark. “It’s a Helluva Townhouse.” Patch. 30 April 2019.

- Gardiner, Sean. “Mounties’ Bounty: Fingerprint tools help nab suspect in NY murders.” Newsday. 31 May 2001.

- Gardiner, Sean. “New Look at Old Cases: Arrest in NJ slayings sparks interest in unsolved homicides.” Newsday. 3 June 2001.

- Gardiner, Sean and Robin, Joshua. “Suspect’s Two Faces.” Newsday. 31 May 2001.

- Hoober, John M. III. “Turnpike murder victim was ex-banker.” Lancaster New Era. 15 May 1991.

- Justia. “State of New Jersey v. Richard W. Rogers.”

- Kahn, Robert. “What Really Happened With the ‘Last Call’ Killer Who Terrorized NYC’S Gay Nightspots in 1980s and ‘90s?” A&E TV. 10 March 2021.

- Kaneley, Reid. “Murder victim’s wife stumped for a motive.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. 18 May 1991.

- Lambiet, Jose. “Victim’s date with death.” Daily News. 6 August 1993.

- Leonard, David E. “Spencer remembered.” The Bangor Daily News. 22 June 2001.

- Lueck, Thomas J. “As Killer Faces Sentencing, His Motive Remains Elusive.” The New York Times. 31 May 2001.

- Maine Encyclopedia. “Orono.” 2023.

- Maine Encyclopedia. “University of Maine.” 2023.

- McAlary, Mike. “He’s the ‘Last Call Killer:’ A chilling profile of new serial slayer.” Daily News. 9 August 1993.

- Northeastern Section: American Chemical Society. “Claude Spencer: In Memoriam.” 25 April 2014.

- Obituaries. “Louise Spencer.” The Evening Sun. 2013.

- Obituaries. “Claude F. Spencer.” The Evening Sun. 2014.

- Parry, Wayne. “Ex-UM student charged in dismemberments.” The Bangor Daily News. 22 June 2003.

- Press Burea. “9 Score High On Merit Test.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 24 October 1967.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Gay Killings Clue.” Newsday. 8 August 1993.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Gay Killer’s Live Dates Sought.” Newsday. 25 August 1993.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Serial Slayer’s Profile: Killer preying on gays called smart, cunning.” Newsday. 21 August 1993.

- University of Maine Catalog for 1973. University of Maine, Office of Student Records. 1973.

- University of Maine Prism. 1973.

- Weir, Richard; McPhee, Michele; Goldiner, Dave. “Drugged, tied, attacked: Cops link 1988 S.I. assault to suspect in 2 gay slayings.” Daily News. 31 May 2001.

- Wright, Jim. “Indictment in Student Slaying.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 9 May 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Murder Charge Dismissed in Maine.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 2 November 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Service Is Saturday For Slain Collegian.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 3 May 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Verdict of Innocent Returned in Slaying of Norwich Man.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 3 November 1973.