For the majority of the eight million residents of New York City, May 28, 2001 was a day like any other. Rain covered the island of Manhattan as the Twin Towers, the highest structures on the horizon, looked over the city. At Mount Sinai Medical Center on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, just steps away from the historic Central Park and Madison Avenue, New York police officers approached one of the long-time nurses in the middle of his shift.

At that moment, Richard Westall Rogers Jr. was unaware that a task force from New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had been tracking him for three weeks. And Richard did not know that eight years of investigation and advancements in forensic technology had finally identified his fingerprints on green garbage bags found on the side of the road in all three of those states – garbage bags containing the remains of four different men.

Perhaps Richard Rogers believed that enough time had passed. Perhaps his experiences with the law thus far made him believe he could and would get away with anything. After all, Richard Rogers had been on trial before, for murder even, and he got off scot free. But his arrest for that confessed killing would eventually play a big role in finally tracking him down 28 years later.

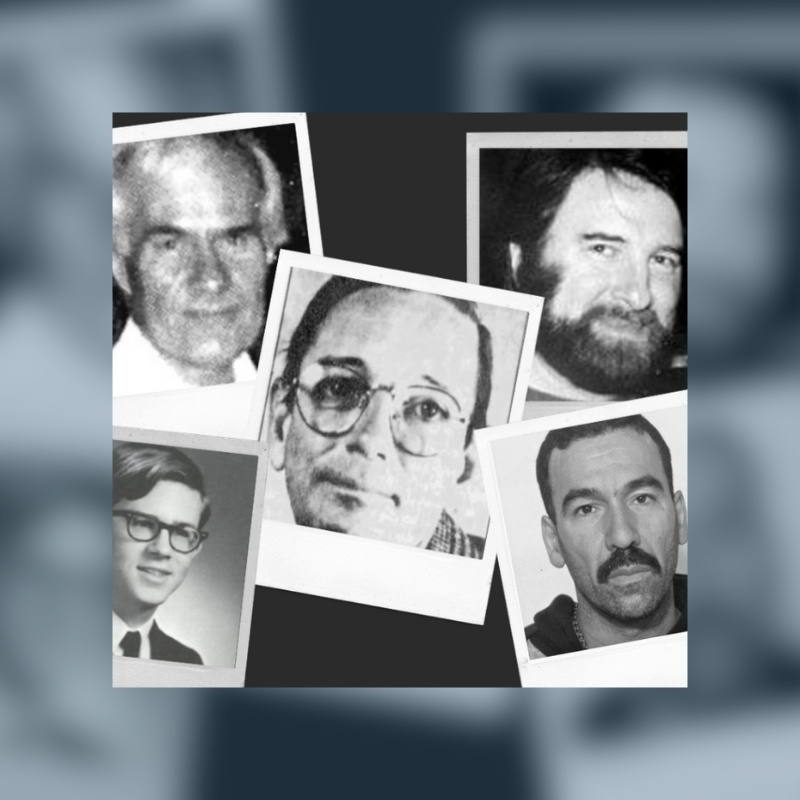

I’m Kylie Low and these are the stories of Peter Stickney Anderson, Thomas Mulcahy, Anthony Edward Marrero, and Michael Sakara on Dark Downeast.

A New Life for Richard Rogers

Richard Westall Rogers Jr. knew that Orono, Maine was a small town in the middle of a close knit state. After he confessed but then was acquitted for the murder of his roommate, Frederic Alan Spencer, Richard disappeared from Maine to create a new life.

Though Rogers had pursued the study of French in both his undergraduate and graduate education, something seemed to change for him. Rather than returning to the occupation or locations that he had previously known – his childhood home in Massachusetts, his parents or college in Florida, or his graduate university in Maine – Richard Rogers moved to New York City. While there, he pursued another, different graduate degree. This time, he enrolled in nursing school at Pace University, graduating in 1978. By January of 1979, soon after his graduation, Richard was hired at Mount Sinai Medical Center and began to establish himself in New York.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Richard Rogers seemed to have found his niche. According to Elon Green’s book “Last Call”, Rogers worked the late shifts at Mount Sinai every other day, meticulously saving his paid time off in order to travel each year. Though he was previously labeled quiet through high school and college and not very well known by his classmates, in New York, Rogers seemed to find himself. While he did not freely discuss his personal life at work, Richard Rogers was openly gay and spent a great deal of his free time frequenting the most well-known gay bars in Manhattan.

More than anywhere else, Richard Rogers was known at The Townhouse Bar. The Townhouse was a piano bar in Midtown Manhattan that catered to an older population of queer men in New York, often attracting businessmen and those visiting town. Still open today after more than thirty years, The Townhouse’s website offers upscale elegance and encourages its patrons to “dress to impress.” In the early 1990s, The Townhouse offered a safe haven for the community and a place for gay men to meet one another.

The atmosphere in New York City in the early 1990s for LGBTQ+ individuals, especially gay men, was full of violence, discrimination, and stereotyping. The New York City Anti-Violence Project (AVP), often cited in Green’s “Last Call”, was formed in the 1980s due to an increase in violence against gay men in Chelsea, Manhattan.

From the beginning, the AVP noted that violence against the queer community was less likely to be investigated by police officers and even less likely to be publicized. The organization fought, and continues to fight, for the safety and freedom of “all lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and HIV-affected people.”

New York City crime, in general, experienced an uptick during this era. The latter half of the 1900s had not been so kind to the city, and it was often thought of as a dangerous destination. According to a New York Times article by George James from April 23, 1991, a new record was set by the number of killings in the city during 1990.

The increase in crime during the early 1990s wasn’t unique to New York though. Neighboring states saw violence creep up in tandem. An August 9, 1991 edition of the Philadelphia Daily News noted, “Crime in Pennsylvania increased 4.1 percent last year over 1989… And of the state’s 802 murders, 503 occurred in Philadelphia.”

Just below this clipping appeared an advertisement for a reward. It read: “The Gay and Lesbian Center has offered a $1,000 reward to help crack the May murder of Center City socialite Peter Stickney Anderson, 54.”

Peter Anderson

Peter Stickney Anderson was born on March 14, 1937. Though he was originally from Wisconsin, Peter had lived around the Northeast, including Dedham, Massachusetts, and New York City, throughout his adult life. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Peter was, “a jovial and proper gentleman, a blue blood, a Trinity College graduate, a bow-tied Son of the Revolution who traced his lineage to Asa Stickney, a Massachusetts private in the Continental Army.”

Peter was an accomplished individual with a loving family and a strong and supportive group of friends. While living in Philadelphia, he spent most of his time at his home at the Wanamaker House, a fashionable apartment building with an excellent location in the city. He was very involved as a member of the First Troop of the National Guard, was engaged in social and political fundraisers and events, and was well-respected in his circles.

Prior to his move to Philadelphia, Peter had worked as a banker and portfolio manager for several brokerages and financial institutions. He made a good living with his education and his work, though his wife commented in the Philadelphia Inquirer that he had come from old family money in New England.

Peter’s second wife agreed to speak with the Philadelphia Inquirer about him on the condition that her information remain private, as she and Peter had been separated for a few years. However, they remained in contact and were on good terms. Peter remained involved in his children’s lives and was a strong father figure. Peter’s wife described him as a “gentleman,” and the Inquirer reported that other friends described him as, “a British-mannered history buff active in social organizations, philanthropy, and local politics” and as someone who “had a reputation for compassion, generosity and good humor.”

But the Philadelphia Inquirer also shared that friends and family worried about Peter. In the final months of his life, Peter had begun to drink more frequently, and many friends noted that he seemed to be experiencing some health problems. Nevertheless, he was still social and loved going out in Philadelphia and New York City, where he was known to frequent bars that catered to the gay community.

On the evening of May 3, 1991, Peter attended a political fundraiser in New York City. According to “Last Call,” Peter met a former roommate at the fundraiser that night and after the event, the pair continued the party at some of the popular gay bars in Manhattan, including The Townhouse.

After several drinks, Peter and his former roommate decided to call it a night. Peter’s friend brought him to a hotel, encouraging him to check-in. However, hotel staff indicated that when they last saw Peter Stickney Anderson, he was leaving – presumably to continue his night. When on the next night, May 4, Peter didn’t appear at his usual haunts, his friends began to worry.

On May 5, 1991, maintenance workers cleaning alongside the Pennsylvania Turnpike discovered a 55-gallon trash barrel by a pull off from the highway in Lancaster County. When one worker tried to remove the trash bags from the barrel, he found that one of the bags was particularly difficult to remove. He opened it to find the mutilated remains of a man.

Though police weren’t immediately sure who the man in the bag was, a match to National Guard registration records later identified the body as Peter Stickney Anderson. His death was labeled a homicide.

Peter Stickney Anderson was laid to rest in Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, close to his roots and not far from his beloved Trinity College. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that at his memorial service, Reverend Tim Dobbins said to the mourners, “How could such a brilliant and talented man die such an ignominious death? In days such as these, the silence seems to scream.”

Upon discovering the fate of her husband, Peter’s wife told the Inquirer that “it was impossible to imagine why anyone would want to kill” him. Peter’s friends found the situation challenging to believe, too. For his entire community, the death of Peter was devastating. Further devastating was the fact that all those who knew and loved him would not have answers about the last hours of Peter’s life for more than ten years. And during that decade, another similar murder would devastate the neighboring state of New Jersey.

Thomas Mulcahy

Thomas Richard Mulcahy was born on July 24, 1934, in Boston, Massachusetts. Thomas’s mother, Mary, had immigrated from Ireland, and like many Irish Catholic families during this time period, Mary believed strongly in the importance of education. Thomas attended Boston College High School during his teen years and then pursued his bachelor’s degree in psychology at Boston College, followed by graduate school at Fordham University in New York City.

During his time at Boston College, Thomas met a woman named Margaret Mary Casey. The pair began dating soon after they met, eventually marrying in 1958. Thomas and Margaret shared four children and remained happily married for more than three decades, settling together to build their lives in Sudbury, Massachusetts.

Thomas was constantly traveling for work as the director of international account sales for a computer company called Bull HN Information Systems, Inc. According to Elon Green’s “Last Call,” Thomas’s wife Margaret discovered more than a year prior to his death that Thomas spent time in gay bars when he was traveling for work. While this was a topic of discussion for the pair in therapy and did put a strain on their relationship, it did not seem to impact how Thomas showed up for his family. He was always a supportive husband and an excellent father.

In July 1992, Thomas was in New York for a professional presentation on July 8, 1992. After the success of the meeting, Thomas decided to go out in the city with one of his coworkers to celebrate. Eventually, he parted ways with the coworker and decided to pop into a few of the city’s gay bars on his own. The last place that Thomas was seen alive was at The Townhouse Bar.

By the evening of July 9, 1992, Margaret Mulcahy had begun to worry that her husband had not yet returned home. By the morning of July 10, she learned why.

On the morning of July 10, 1992, maintenance workers in Woodland Township, New Jersey drove along Route 72, pulling over to the side of the road to collect trash whenever they spotted trash cans. Though a couple of the bags seemed unusual, the workers continued along their typical route until finally opening one of the strange bags. Inside, the workers found human remains. Four other bags were also found to contain remains and personal items, including a briefcase and wallet. They belonged to Thomas Richard Mulcahy. His death was ruled a homicide.

At his funeral a week later at Our Lady of Fatima Church in Sudbury, Massachusetts, Thomas’s daughter, Tracey, said, “It is ironic that someone filled with so much love was taken from us in a crime by someone filled with so much hate.”

It was difficult for Thomas’s family to wrap their minds around what happened to their loving father, brother, and husband. The Boston Globe reported that Thomas was thought of as “a man whose compassion for humanity caused him at times to cry while watching the daily offerings of world violence on television news.” Thomas’s children still speak of him publicly and lovingly years later.

For investigators in New Jersey, the discovery of Thomas’s remains seemed familiar. They reached out to Pennsylvania police, citing the similarities in this case to that of Peter Stickney Anderson just over a year prior. Both Peter and Thomas frequented gay bars but did not publicly identify as gay, they had wives and families, they were in their fifties, and both of the men were professionally successful. Both had last been seen out in Manhattan, and both were found two days later in garbage bags by the side of the road. Yet despite the beginnings of a traceable pattern, both offices had yet to identify a motive.

One year later, a third homicide with similarities to the cases of Thomas Mulcahy and Peter Anderson confounded investigators. Were police dealing with a serial killer?

Episode Source Material

- Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York by Elon Green

- Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York on HBO

- Associated Press. “3 Counties’ Scholarship Winners.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 14 February 1968.

- Associated Press. “Arraignment Held in Murder Case.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 4 May 1973.

- Associated Press. “Body found along Pike.” The Evening Sun. 23 January 1992.

- Associated Press. “Dismembered body identified as Massachusetts sales executive.” UPI Archives. 13 July 1992.

- Associated Press. “‘Evil’ ex-Mainer gets consecutive life terms.” Sun Journal. 28 January 2006.

- Associated Press. “Mounties help ID prints in gay killings.” The Bangor Daily News. 1 June 2001.

- Associated Press. “Pa. crime up 4.1%.” Philadelphia Daily News. 9 August 1991.

- Associated Press. “Pattern in a Trail of Death.” Hartford Courant, 1 June 2001.

- Associated Press. “Police: Serial killer may stalk gay men.” News-Journal. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Police suspect killer stalking gays.” The Berkshire Eagle. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Serial killer may have slain 4 gay men, authorities say.” The Akron Beacon Journal. 5 August 1993.

- Associated Press. “Socialite found dead in trash can was ‘a lost soul.’” The Philadelphia Inquirer. 10 June 1991.

- Associated Press. “Student is found innocent in Orono beating death.” Daily Kennebec Journal. 5 November 1973.

- Associated Press. “Student’s Trial This Fall.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 1 October 1973.

- Associated Press. “Technology May Provide Link to Suspected Serial Killer.” Hartford Courant, 2 June 2001.

- Bennett, Troy R.; Degre, Gabor; Feulner, Brian; Harrison, Judy; McCrea, Nick; Moretti, Mario. “Charlie: Thirty years after the killing of a young gay man shocked Bangor, his death is now remembered for its profound effect on Maine.” The Bangor Daily News. June 2014.

- Burnham, Emily. “Charlie Howard murder dramatized in ‘It’ sequel.” Foster’s Daily Democrat. 4 September 2019.

- Cave, Damien. “As Killer Faces Sentencing, His Motive Remains Elusive.” The New York Times. 27 January 2006.

- Choice. “What Happened To New York: A History Of The 00’s So Far.” Gawker. 31 December 2007.

- Clinton, Roger. “2nd body found at turnpike.” Intelligencer Journal. 22 January 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Friends, family gather to mourn Sudbury man.” The Boston Globe. 17 July 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Police recover belongings of slain Sudbury man.” The Boston Globe. 15 July 1992.

- Coakley, Tom. “Police seeking motives in dismemberment.” The Boston Globe. 17 July 1992.

- Curran, John. “Former Maine man gets consecutive life sentences.” Foster’s Daily Democrat. 27 January 2006.

- Dawson, Mark. “It’s a Helluva Townhouse.” Patch. 30 April 2019.

- Gardiner, Sean. “Mounties’ Bounty: Fingerprint tools help nab suspect in NY murders.” Newsday. 31 May 2001.

- Gardiner, Sean. “New Look at Old Cases: Arrest in NJ slayings sparks interest in unsolved homicides.” Newsday. 3 June 2001.

- Gardiner, Sean and Robin, Joshua. “Suspect’s Two Faces.” Newsday. 31 May 2001.

- Hoober, John M. III. “Turnpike murder victim was ex-banker.” Lancaster New Era. 15 May 1991.

- Justia. “State of New Jersey v. Richard W. Rogers.”

- Kahn, Robert. “What Really Happened With the ‘Last Call’ Killer Who Terrorized NYC’S Gay Nightspots in 1980s and ‘90s?” A&E TV. 10 March 2021.

- Kaneley, Reid. “Murder victim’s wife stumped for a motive.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. 18 May 1991.

- Lambiet, Jose. “Victim’s date with death.” Daily News. 6 August 1993.

- Leonard, David E. “Spencer remembered.” The Bangor Daily News. 22 June 2001.

- Lueck, Thomas J. “As Killer Faces Sentencing, His Motive Remains Elusive.” The New York Times. 31 May 2001.

- Maine Encyclopedia. “Orono.” 2023.

- Maine Encyclopedia. “University of Maine.” 2023.

- McAlary, Mike. “He’s the ‘Last Call Killer:’ A chilling profile of new serial slayer.” Daily News. 9 August 1993.

- Northeastern Section: American Chemical Society. “Claude Spencer: In Memoriam.” 25 April 2014.

- Obituaries. “Louise Spencer.” The Evening Sun. 2013.

- Obituaries. “Claude F. Spencer.” The Evening Sun. 2014.

- Parry, Wayne. “Ex-UM student charged in dismemberments.” The Bangor Daily News. 22 June 2003.

- Press Burea. “9 Score High On Merit Test.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 24 October 1967.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Gay Killings Clue.” Newsday. 8 August 1993.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Gay Killer’s Live Dates Sought.” Newsday. 25 August 1993.

- Rashbaum, William K. “Serial Slayer’s Profile: Killer preying on gays called smart, cunning.” Newsday. 21 August 1993.

- University of Maine Catalog for 1973. University of Maine, Office of Student Records. 1973.

- University of Maine Prism. 1973.

- Weir, Richard; McPhee, Michele; Goldiner, Dave. “Drugged, tied, attacked: Cops link 1988 S.I. assault to suspect in 2 gay slayings.” Daily News. 31 May 2001.

- Wright, Jim. “Indictment in Student Slaying.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 9 May 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Murder Charge Dismissed in Maine.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 2 November 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Service Is Saturday For Slain Collegian.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 3 May 1973.

- Wright, Jim. “Verdict of Innocent Returned in Slaying of Norwich Man.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. 3 November 1973.