The chilled, windy air of the Atlantic Ocean surrounded the ship past midnight on July 14, 1896. Bells rung out across the deck every half hour with consistency. Two bells signaled that it was one hour past midnight, four bells that it was two. With every four bells, a change in the shift aboard the Herbert Fuller began.

Nine days into its voyage between Boston, Massachusetts and Rosario, Argentina, all was well aboard the ship, which carried twelve passengers and a boat load of lumber for trade. Just past four bells, however, a single shriek rang out through the back cabin where the officers of the ship resided – the after house. Silent to all but its victims, yet impactful to many beyond those who died, an ax repeatedly fell.

With the exception of the wind, silence returned to the Herbert Fuller. Lester Hawthorne Monks, a young man on leave from Harvard University, hesitated in his cabin, unsure of the source of the scream. When he finally left his room, he found the bodies of Charles Nash, the captain of the ship, his wife, Laura, and the second mate of the ship, August Blomberg.

The next week on the Herbert Fuller was tense, full of suspicion. As the remaining crew returned to the closest port in Halifax, Nova Scotia, little was solved. Accusations flew, but many questions were difficult to answer. Who murdered Charles, Laura, and August? And why?

I’m Kylie Low and this is the historic case of the murders aboard the Herbert Fuller on Dark Downeast.

History of the Herbert Fuller

The year 1896 in the United States was a time of immense change. The industrial revolution had begun two decades earlier and was having a tremendous impact on life in America. The Chicago World’s Fair had taken place just three years ago, and was only the second exposition to be held in America. The United States was finding its place in the world, and trade was especially important, since the country was not self-sufficient.

While technology had begun to take over in many ways – many households routinely used telephones – ships remained the primary means of transportation for cargo that needed to be sent across the ocean.

For those who owned and captained ships, the sea represented a tremendous opportunity. It came with adventure, a reliable job, and the potential to make a fortune. This was also true for the sailors aboard the ship until the middle of the nineteenth century. By 1896, the opportunities associated with sailing and trade had begun to dwindle.

While owners could still be successful, crew members on trading ships began to develop a poor public reputation, were not paid well, and offered little opportunity for promotion. Life on ships could be dangerous, and sailors would sign up for long voyages for low wages, often leaving their friends and family behind for extended periods of time. As a result, many sailors in the United States were originally from other countries, seeking a better life on the ocean.

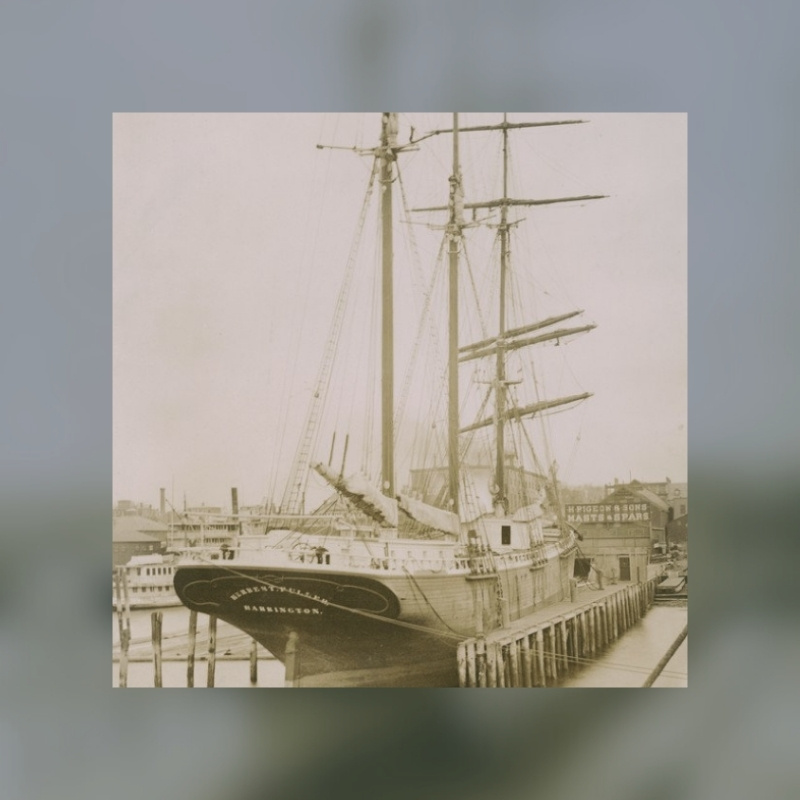

In the case of the Herbert Fuller, the ship was just six years old, having been built in Maine in 1890. In “Murder Aboard,” C. Michael Hiam describes the Herbert Fuller as “an attractive sight” and “a graceful vessel.” It was a large boat that could be operated by eight, but for this voyage, held twelve people alongside its cargo of white pine boards.

When the Herbert Fuller set sail on July 5, 1896, its twelve passengers represented a wide variety of individuals. In the forward house, which was towards the bow – or the front – of the ship, resided Francis Loheac, who was from France; Henry Slice, who was from Germany; Henrik Perdok, who was Netherlands; and Falke Wassen and Oscar Andersson, who were Sweden. Charley Brown, whose real name was Justus Leopold Westerberg, was from Sweden. Jonathan Spencer, who was from the British West Indies, acted as the ship’s Steward, his job primarily consisting of cooking and cleaning as service staff.

The after house was on the stern of the ship, and served as housing for the mates – the leaders – of the Herbert Fuller. August Blomberg, the second mate, was from Finland. He had come to the United States and had been a sailor for just two years, but was a hard worker and had quickly risen up the ranks from sailor to second mate.

But a man named Lester Monks was aboard the Herbert Fuller for reasons that were quite different from most. Monks was from a fairly well-off family in Brookline, Massachusetts, which is part of the Boston metropolitan area. He had attended Harvard University, but had fallen ill before completing his degree. Due to his declining health, his family had recommended that he take time off from school.

Based on familial connections, it was arranged for Monks to sail to Argentina as a guest on the Herbert Fuller. The rooms on the ship were all previously assigned, and rather than ask Monks to sleep with the crew or find a bed elsewhere, the captain of the ship allowed Monks to sleep in the captain’s room. As for Captain Nash, he slept on a bunk in the chart room for the duration of the voyage.

Thomas Bram, the first mate, was from Saint Kitts. He had left home at a young age to pursue the sea, and had led a life of adventure ever since. When Bram was not sailing as a mate or captain, he was working in or managing restaurants. At one point, he pursued opening his own restaurant, but the venture did not last.

Bram was a deeply religious man whose faith was important to him. He was married and had two children, but when he returned to life on the sea, his contact with his family became much less frequent, until his wife hardly heard from him at all.

At the helm of the Herbert Fuller during the summer of 1896 was Charles I. Nash, accompanied by his wife, Laura Ray Nash. Charles and Laura had grown up together in Harrington, Maine and had been married since 1880.

Harrington, which is also where the Herbert Fuller itself had been built, is a small town on the north east coast of Maine, within the Down East region. Today, the population of Harrington is under one thousand people, which has not changed much since the late nineteenth century. In the 1890 Census, the town held just three hundred more people – approximately one thousand, one hundred and fifty individuals who called Harrington home.

Since its founding in the late eighteenth century, the families residing in Harrington have largely been deeply connected to the ocean. The town is known for ship building, along with some agriculture and trade. In the 1890s, the Nash and Ray families led lives on the sea, with many of their children following in those footsteps.

In their sixteen years of marriage, Charles and Laura did not have children. It was because of this that Laura often accompanied her husband as he fulfilled his duties as a ship captain, the two traveling the world together from Maine to Europe to South America. On the Herbert Fuller, they could often be seen walking the deck together in the evening as the sun was going down over the horizon.

According to a July 22, 1986 edition of the Boston Globe, both Charles Nash and his wife were deeply respected in their hometown. Charles was known to be very committed to his work and to take great pride in building and captaining his ships. His wife was described in the paper as “quiet” and “pleasing,” with “absolutely correct habits and the highest character.” She was also known to be kind to the sailors on the ships that her husband captained. It seems that no negative words could be spoken about the pair.

These positive descriptions of Charles Nash, Laura Ray Nash, and August Blomberg only make their deaths more confusing. Aboard a ship afloat in the middle of a voyage in the Atlantic Ocean, filled with individuals many of whom knew each other well – why would someone commit such an atrocity?

July 14, 1896

The Herbert Fuller set sail for Argentina with twelve individuals on board on July 5, 1896. Nine days later, in the early morning hours of July 14, only nine of its passengers were still alive.

All that is known about the events that took place on board comes from the often-conflicting accounts of the survivors who were aboard the ship that night. Many sources lean on the story of Lester Hawthorne Monks, the young college student who was a guest on the ship during that voyage. Interestingly, a great deal of Lester’s narrative matches the book that he was reading at the time – “A Voyage to the Cape” by William Clark Russell, who wrote thrilling stories of dangerous events on the sea.

That night, after falling asleep reading, Lester Monks was awoken by the scream of Laura Nash, who was sleeping just two rooms over in the after house. Though Monks often paraded himself as a hero later, in that moment, he acted from fear. He stayed quiet in his room, not knowing the best course of action. Finally, after several minutes, Monks decided that he should check in with the captain, who was sleeping in the chart room just outside of Monks’ quarters.

When Monks found the captain, it was already too late. Some members of the crew later described the state of Charles Nash as on the brink of death, using the term “death rattle.” Nash had been brutally assaulted and had wounds all over his body, though Monks did not yet know the cause. Seeing this, Lester Monks returned to his room, grabbed his revolver, and left the after house in search of assistance.

The first person he met was Thomas Bram, the first mate. Bram was on duty on deck during that time of night, keeping lookout over the ship while Charley Brown was at the wheel. Monks quietly shouted the mate’s name, keeping his revolver pointed ahead of him. When Bram noticed Monks and his revolver, Bram held up a wooden board and pointed it at Monks, throwing it in his direction. Surprised, Monks lowered his weapon and let Bram know that the captain was dead.

The two men went into the after house, finding the body of the captain and of his wife. Both Charles and Laura Nash had been severely injured, wounds covering a majority of their bodies. By this time, both were near death if they hadn’t succumbed to their injuries already.

Though the murder weapon had not yet been found, the gashes on their bodies and the amount of blood clearly indicated that an ax was used. According to Monks, he suggested to Bram that they find the second mate – he would’ve been next in rank after Bram on the Herbert Fuller – but Bram said that he had already seen the second mate walk towards the quarters at the bow of the ship. There was no need to check on him, Bram implied.

Before speaking to any other members of the crew, Monks and Bram feared that there may be a mutiny in progress that had resulted in the murder of the Captain and his wife. If this were the case, Bram told Monks, he was afraid that he would be the next subject since he was the first mate, and he confessed that he had not always been kind to the members of the crew.

The following hours were tense. The two kept out of sight, but in their waiting for sunrise, Bram actually located the ax believed to be the murder weapon. He later claimed that he threw it overboard for fear that the crew would use it against him. The two men sat together through the night until the sun came up, when they decided to speak to Spencer, the steward.

The “Official” Theory

Spencer joined Monks and Bram, and the trio investigated the room of August Blomberg where they found the second mate dead, the area above his door damaged with the blade of an ax and his body in the same state as the captain and his wife.

The three finally went to the remainder of the crew to deliver the horrible news about what they’d found. After some debate, the crew decided that in light of the circumstances, they would forgo their voyage to Argentina and return to the nearest port. Considering the waves and the wind, they chose to sail to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Concerned with keeping all three bodies on board, the men decided against a burial at sea and chose to use one of the small boats on the Herbert Fuller to keep the deceased with them. They laid the three in the boat, covering it with tarp and lowering it to tag along behind the ship on the remainder of their voyage.

Once they had laid their plans, the crew contemplated a theory regarding what may have occurred that night. Though suspicions were high, either from fear or an unwillingness to believe that a murderer could still be aboard with them, the group chose to pursue a theory where no living people were implicated.

The nine men wrote their theory as an entry in the ship’s logbook, which was kept on trading vessels to maintain record of the ship’s passage and occurrences aboard. Lester Monks wrote it out, ostensibly because he had the best handwriting, though several spelling and grammatical errors occurred in the entry. All nine men signed the paper.

According to this entry, the remaining crew and Monks theorized that the second mate, August Blomberg, had gone to the room of Laura Nash that night to assault her. When her body was found, her dress had been pushed up to her knees, which fueled this theory, though no other evidence indicated assault and the position of her dress may have been a result of her fighting back when she was murdered. Regardless, the entry states that when Laura awoke, she screamed, and her husband came to her defense, attacking Blomberg with an ax. They wrote that Blomberg and Nash had fought and injured one another, as well as Laura, so extensively that all three had passed away.

Though all nine men signed, several later stated that they were not fully on board with this theory. After all, this would hardly make sense and would not explain how Blomberg had made it back to his room without leaving a trail of blood, why the cot in the chartroom where Captain Nash had been sleeping had been tipped over, or how all three had perished. These remaining suspicions would show up in the following days.

Before long, and despite the official theory entered into the log book, suspicion began to fall on Charley Brown, or August Leopold Westerberg. Brown had been at the wheel that night, meaning that he had been alone and therefore could not provide an alibi.

Members of the crew also remarked that Brown was odd. He often spoke or sang to himself, and told the other men on board that he had once been institutionalized for shooting a man. The crew took action and captured Brown, chaining him to a mast for several days until Brown had a new story to share. He told the crew that while he was at the wheel of the ship that night, he watched as Thomas Bram raised an ax above his head in the chart room. That accusation was enough for the crew of the surviving crew of the Herbert Fuller. Shortly thereafter, Bram was also tied up to a mast.

One week after Lester Monks had woken to the sound of a scream and discovered the bodies of most of the residents of the after house dead on board, the Herbert Fuller arrived on land in Nova Scotia. The ship and its passengers were immediately taken into custody as the law decided how to move forward.

The police in Halifax kept everyone from the Herbert Fuller under lock and key as the investigation began. Without the murder weapon and with little evidence beyond the stories of the crew and of Lester Monks, it was difficult to know anything for certain. Interviews began – but from the beginning, not everyone was treated equally.

Episode Source Material

- Associated Press. “BRAM GETS A NEW TRIAL; Supreme Court Reverses the Verdict in the Case of the Herbert Fuller Sea Murders. ADMITTED WRONG TESTIMONY. The Confession Made to Detective Powers in Halifax by Implication Should Not Have Been Considered.” New York Times. 14 December 1897.

- Associated Press. “Capt Thomas Bram Will Claim Trunk Figuring in Murder Trial.” The Boston Globe. 28 January 1929.

- Associated Press. “Cotter’s Final Struggle.” The Boston Daily Globe. 31 December 1896.

- Associated Press. “Court Denies Request: Mr. Cotter Renews Effort to Secure Night View of the Herbert Fuller.” The Boston Globe. 21 March 1898.

- Associated Press. “Evidence All In.” The Boston Daily Globe. 30 December 1896.

- Associated Press. “Monks to be Called Today: That is the Expectation of the Bram Counsel – Steward Spencer on the Stand.” The Boston Globe. 22 March 1898.

- Associated Press. “Monks’ Story of the Beginning of the Fatal Voyage.” The Boston Globe. 22 March 1898.

- Associated Press. “Mutiny and Murder.” The Boston Daily Globe. 22 July 1986.

- Associated Press. “Story of the Crime: Cook of the Herbert Fuller Testifies.” Boston Evening Transcript. 21 March 1898.

- Bram v. United States, 168 U.S. 532 (1897). U.S. Supreme Court.

- Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online. “Barkentine ‘Herbert Fuller’, wharf near 81 Summer St., East Boston, ‘at time of trial for the murder of the captain.’” Photograph. 1896.

- German, Andrew W. “Maritime Activities in American History—An Introduction.” Excerpted from Voyages: Stories of America and the Sea. Mystic Seaport Museum. 2000.

- Gordon, Bob. “Book Excerpt: The Bad Detective.” Unravel Halifax. 29 November 2021.

- Grinnell, Charles E. “Why Thomas Bram Was Found Guilty.” The Green Bag. 1897.

- Hiam, C. Michael. “Murder Aboard: The Herbert Fuller Tragedy and the Ordeal of Thomas Bram.” Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

- Koeppel, Gerard.” Not a Gentleman’s Work: The Untold Story of a Gruesome Murder at Sea and the Long Road to Truth.” Hachette Books, 2020.

- Koeppel, Gerard. “The High Seas Murder That Shocked – And Baffled – The World.” Crime Reads. 2020.

- Library of Congress. “America at the Turn of the Century: A Look at the Historical Context.” 2023.

- New England Historical Society. “Fiction Becomes Fact – Murder on the Herbert Fuller.” 2021.

- Rinehart, Mary Roberts. “Mary Roberts Rinehart Believes That Bram Was Not Guilty of Murders.” The Boston Sunday Globe. 22 March 1914.

- Rinehart, Mary Roberts. “The After House: A Story of Love, Mystery and a Private Yacht.” 1914.