I created Dark Downeast to tell the true crime cases and mysteries prickling New England’s history that maybe you’ve never heard of, either because they’ve simply faded into time, or maybe they’re kept hush-hush so as not to taint the reputation of a small town.

This case could be a little of both. Here’s the thing, this could’ve been a cold case on the list. By definition, a cold case is one that remains open but is not actively pursued unless new evidence is discovered. One of the victims in this case, from nearly 100 years ago, is unlikely to ever see a resolution. All of the major players in the story have passed, and the key suspect? She died before a verdict could ever be reached. This is the story of Lottie Cote, the most murderous woman in North Gorham.

Down East Siren

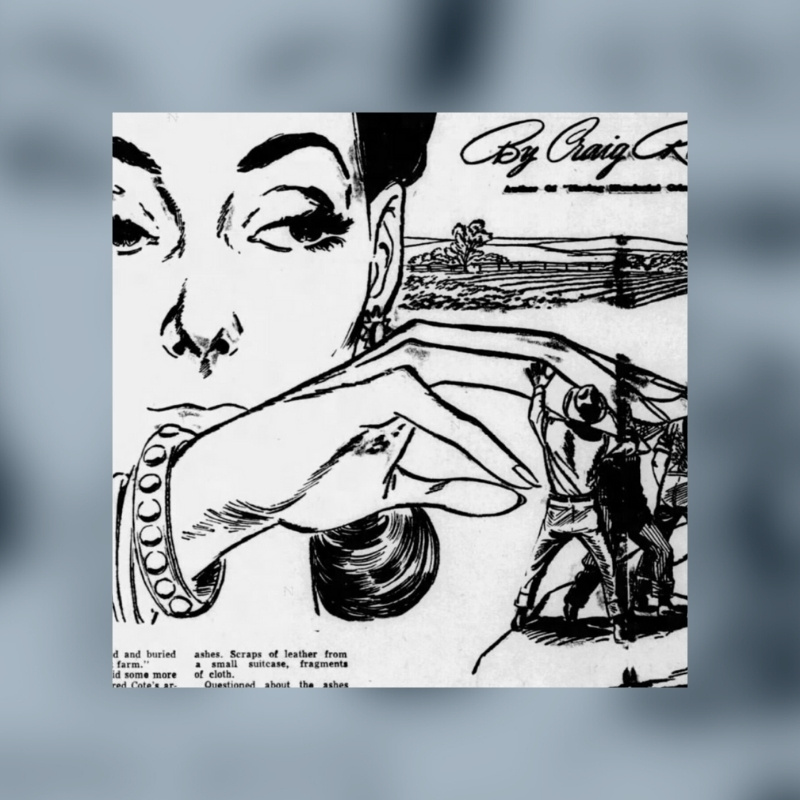

A piece in The Orlando Sentinel, written by Craig Rice published on June 22, 1952, is accompanied by an illustration of a larger than life woman. She is glamorously styled, with a classic 1920s ‘do, dramatic arched eyebrows and thick curled eyelashes. Apparent farmland extends behind her, but she doesn’t look “off the farm”. Instead, she’s wearing art deco era jewelry, with big sparkly earrings and gem-studded bangles on her wrist. And extending from her wrist is her well-manicured hand… Her fingers extended, toying with four miniature men that she cups in the other. On her ring finger is a wedding band.

The depiction of the glamorous woman with her handful of men, is of Lottie Cote. Craig Rice’s article calls her the Down East Siren. But that name gives her the allure of red-hot, black and white film love interest, or maybe the damsel who is in much distress and by the end of the story, she’s rescued and twirled and dipped into a deep kiss as the credits roll.

But that wasn’t Lottie Cote. She may’ve been the love interest of many men, but Lottie was not in distress. And the only thing red-hot was the blood on her hands. In 1925, in North Gorham, Maine, Lottie Cote couldn’t stop killing her husbands.

Who is Lottie Cote?

Lottie Cote was born Lottie Freeman sometime around 1880 to prominent and respected parents. Their family might’ve been categorized as “well-to-do” at the time, given their landowner status of a sizable farm in North Gorham.

Lottie was a beautiful young woman, according to reports… And coming from a well-off family made her doubly attractive to male suitors. She was often the talk of the town, too, for all the attention she received from eligible bachelors. Craig Rice said in her piece for the Orlando Sentinel that when Lottie finally chose the man who would become her husband, “The unmarried girls breathed secret sighs of relief that she would no longer offer them competition.”

Lottie married a man named William Sanborn sometime after 1901 (that’s Sanborn without a d, I believe, but it’s spelled with it in some places). Chris and I just hit our one year anniversary and we heard two polar opposite stories about the first year of marriage — It can either be the most blissful honeymoon phase, or it can be the most challenging… I’d say for my marriage, it was pretty blissful, despite, you know, a pandemic and relocating unexpectedly and learning to work from home together and a recession and all those things. But yeah, pretty blissful relationship-wise.

But for Lottie and William, if small town gossip was anchored in truth as it often is, the first year was riddled with lies and secrets. It seems as though Lottie had no interest in settling down after saying “I do.” The rumors continued that she went about her premarital ways, going on secret dates with other men and drumming up a fair amount of scandal for herself.

Her First Husband

By the summer of 1910, the beautiful young Lottie was the mother of three children by William, named Roland, Ralph, and Susie. And the once scandalous and rumor-ridden life of Lottie only spiraled deeper into a story of mystery and speculation. Her husband and father of their children, William Sanborn, was missing.

On June 20, 1910, Lottie sat in the Sheriff’s office, wiping away her tears as she reported his disappearance, but Lottie didn’t hold back with her suspicions as to why he left. You see, Lottie’s well-to-do parents had left her the farm, and with it came the family fortune. She suspected that William had always been obsessed with her money, and had forged her name on some notes but couldn’t pay the balance due himself, so he took off, leaving his wife and three children behind.

The Sheriff apparently took Lottie’s story for fact, because no investigation was done into the disappearance of William Sanborn… At least not for another decade.

But the small town talked, as a small town does, and even Lottie herself contributed to the swirling gossip around her husband’s disappearance. Her story changed depending on her audience — She told William’s brother in a letter that he had been sent away to a prison in Tennessee. But that prison had no record of William Sanborn as an inmate.

And Lottie told friends that William simply went to a show in Portland one night, maybe the circus, and never returned home.

The changing stories were suspicious, and the finer details were curious, too. William was always dressed to the nines, but he left his best clothing at home when he left. He also left behind his pipe, which would’ve been like leaving home without your phone today. William always had his pipe.

Still, no further investigation was done immediately following his reported disappearance. And in the years following his disappearance, Lottie filed and was granted a divorce from her first husband on grounds of desertion. Just in time for her to marry again.

For the entire Lottie Cote case, and what happens next in one of the most sensational murder cases in Maine’s history, hit the play button on the player above or find the episode wherever you get your podcasts.

Cote House, Gorham, 1924. Photo Source: MaineMemory.net

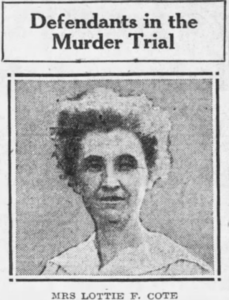

Lottie Cote Mug Shot Photo. Source: The Boston Globe

Cote farm search, Gorham, 1924. Photo Source: MaineMemory.net

Explosives used during Cote murder investigation. Photo Source: MaineMemory.net

Man standing over dig site, Cote murder investigation. Photo Source: MaineMemory.net

Men digging during the Cote murder investigation. Photo Source: MaineMemory.net

Episode Source Material

- Down East Siren, 1952 Article in The Orlando Sentinel by Craig Rice

- The Bangor Daily News, Nov 1924

- The Bangor Daily News, Feb 16, 1925

- The Boston Globe, Feb 20, 1925

- The Burlington Free Press, Feb 21, 1925

- The Burlington Free Press, Mar 3, 1925

- The Burlington Free Press, Nov 18, 1925

- The Barre Daily Times, Dec 17, 1925

- MaineMemory.net Artifact 74600

- MaineMemory.net Artifact 74601

- MaineMemory.net Artifact 74605

- MaineMemory.net Artifact 74603

- MaineMemory.net Artifact 74602